Article: Odin: The Allfather in Germanic Myth, Literature, and Cult

Odin: The Allfather in Germanic Myth, Literature, and Cult

Odin, or Wōðanaz in Proto-Germanic, is arguably the most widely attested deity of the Germanic world. Across Scandinavia, England, and the continental Germanic lands, he appears as god of war, wisdom, poetry, magic, and death. Unlike gods tied to a single domain, Odin’s character is protean, shifting in emphasis depending on cultural context, literary source, and historical period. From the earliest Roman accounts to the late medieval sagas, Odin embodies the ideals and anxieties of the Germanic peoples: the drive for honor, the inevitability of fate, and the pursuit of knowledge at any cost.

Origins, Name & Sources

The name Wōðanaz is rooted in the Proto-Germanic term wōð- meaning “fury” or “inspired frenzy,” reflecting his association with ecstatic states, battle frenzy, and prophetic insight. Variants appear throughout the Germanic world: Wodan in Old High German, Goden among the Lombards, Óðinn in Old Norse, and Woden/Wotan in Old English. These linguistic continuities point to a shared mythological core, even as regional traditions added new attributes. Scholars have speculated that the name also preserves echoes of a historical chieftain figure, who may have led migrations or exerted cultic authority among early Germanic tribes.

Odinskopf (Odin’s head), C.E.12th - 13rd century. Located in Old Town, Historical Museum of Oslo (Photo: Hermann Junghans CC BY-SA 3.0)

Odin in Early Historical Sources

Tacitus, writing in the first century CE in Germania, describes the chief god of the Germanic tribes as Mercury, who received human sacrifices. Scholars widely identify this Mercury with Odin/Wodanaz, noting similarities in domains: travel, communication with the dead, and magical prowess. Tacitus’ account emphasizes Odin as a god who leads and inspires warriors, highlighting his centrality to tribal cohesion.

By the 11th century, Adam of Bremen provides a Christianized perspective in his description of the temple at Uppsala, where sacrifices to Wotan, Thor, and other deities were conducted. Adam portrays Odin as a distant, commanding figure, demanding obedience and tribute, further cementing the association of Odin with kingship, war, and fate.

Odin in the Poetic and Prose Eddas

Old Norse literature preserves Odin in extraordinary detail. In the Poetic Edda, particularly in Völuspá, Odin appears as a seeker of wisdom, consulting a völva to learn of the future and of Ragnarök, the end of the cosmos. He sacrifices one eye at Mímir’s well to gain knowledge and hangs himself upon Yggdrasil in Hávamál to learn the secrets of the runes. These narratives emphasize that Odin’s power is inseparable from suffering and self-denial.

In Grímnismál, Odin, under the guise of “Grímnir,” reveals the structure of the cosmos while enduring torture by King Geirröðr, reinforcing his role as a teacher and mediator of divine knowledge. Vafþrúðnismál depicts Odin engaging in a contest of wisdom with the giant Vafþrúðnir, highlighting his intelligence and cunning. Similarly, in Baldrs draumar, he ventures to Hel to uncover Baldr’s fate, combining his roles as protector, father, and seer.

Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda (13th century) synthesizes these myths with euhemerized interpretations, presenting Odin as chief of the Æsir and a culture-bringer. In Gylfaginning, he orchestrates creation, guides heroes, and presides over the events of Ragnarök. Skáldskaparmál depicts him as the instigator of the mead of poetry, while Háttatal acknowledges his patronage over the skaldic art form. Across these texts, Odin is simultaneously god of wisdom, war, and magic — a versatile figure reflecting the complex worldview of the Norse.

Odin's Role As a Deity & Ancestor

Odin in diguise places a sword into the tree Barnstokkr in the hall of the Völsungs (Photo: Emil Doepler).

In the legendary sagas, Odin’s influence extends into human affairs, often as an ancestral figure. The Ynglinga saga, part of Snorri’s Heimskringla, presents Odin as an ancestral king of the Swedes who is later deified. Similarly, Anglo-Saxon genealogies trace royal lineages to Woden, asserting divine legitimacy. The Völsunga saga shows Odin’s direct hand in the hero cycle: he plants a sword in the great tree Barnstokkr, which Sigmund alone can draw; in Sigmund’s last battle Odin appears and sets his spear before him, causing the blade to shatter and sealing the hero’s fate. Hjörðis preserves the fragments, and when Sigurðr later has them reforged, the weapon is named Gram. In sagas such as Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks and Hrólfs saga kraka, Odin likewise tests rulers with riddles or bends outcomes from the shadows, underscoring his omnipresence in Germanic ideas of destiny and, in Sigmund’s case, his personal “claiming” of chosen warriors for Valhalla.

God of War and the Dead

Odin’s martial aspect is central. In Eiríksmál and Hákonarmál, he receives slain kings into Valhalla, preparing them for the final battle at Ragnarök. He is assisted by valkyries, who select those worthy of this honor, reflecting the social importance of valor and battlefield excellence. Archaeological evidence, including weapons in burial mounds, corroborates the emphasis on warrior cults.

Continental Germanic sources attest to similar beliefs. The Merseburg Charms (9th century) depict Wodan as a healer and protector, while Paul the Deacon’s Historia Langobardorum recounts Wodan and his wife Frea guiding the Lombards to victory. The Saxon Baptismal Vow (8th–9th centuries) demonstrates the Christianization process, wherein converts explicitly renounced Thunor, Saxnôt, and Wodan.

Jelling Art Óðinn Totem Amulet

God of Wisdom, Poetry & Magic

Odin’s domain extends beyond war into the intellectual and artistic. In Hávamál, he teaches moral maxims, runic lore, and strategic thinking, linking wisdom to sacrifice. The theft of the mead of poetry (Skáldskaparmál) further illustrates Odin’s role as patron of creativity. He is associated with seiðr, a shamanic form of magic that transgresses conventional gender and social norms. Through these practices, Odin mediates between the known and unknown, providing both inspiration and protection to his followers.

Skaldic poetry reinforces these qualities. Kennings and invocations, such as “Viðris veðr” (Odin’s storm = battle) and “Sigföðr” (Father of victory), appear repeatedly in 9th–10th century texts like Hrafnsmál and Haustlöng. They depict him as the archetypal Germanic figure: simultaneously violent, cunning, poetic, and fate-bound.

Regional Variations

Odin’s identity adapted across the Germanic world. Among the Anglo-Saxons, Woden was both ancestor and god, appearing in royal genealogies and charms such as the Nine Herbs Charm. Continental Germanic tribes worshiped Wodan with local modifications: in Old High German, Wodan receives cultic veneration, while in Lombard traditions, Godan/Goden appears in origin myths. These variations illustrate the mobility of Odin’s cult and its integration into diverse social and political contexts.

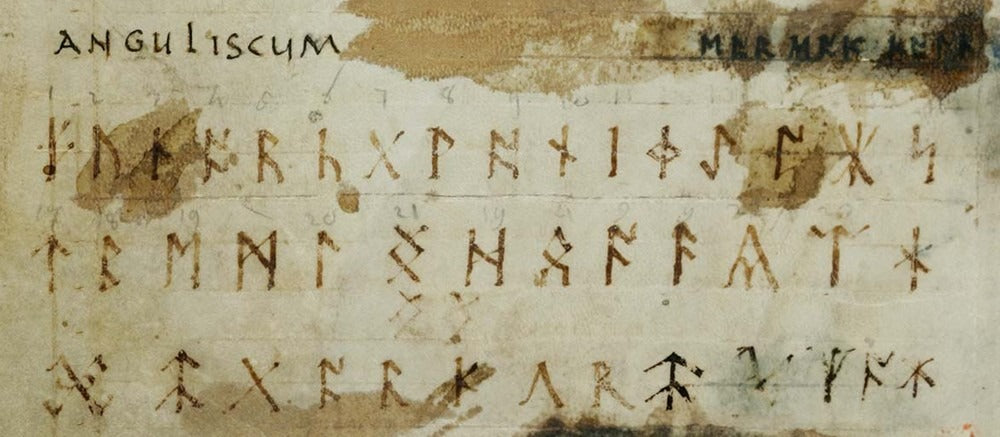

Runes & the Power of Speech

Among Odin’s most distinctive attributes is his intimate connection to the runes, not merely as symbols of writing but as embodiments of cosmic power, sound, and meaning. In Hávamál, he recounts how he sacrificed himself to himself, hanging from Yggdrasil for nine nights, pierced by his own spear, without sustenance or aid. This self-inflicted ordeal was a ritual of extreme knowledge-seeking, through which he learned the secrets of the runes — the letters, the sounds, and the forces they represent. These runes, most notably preserved in the Elder Futhark, are more than a script; they are channels of magic and speech, capable of shaping reality through articulation, song, and incantation. Later adaptations, including the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, extended this system while retaining the connection between spoken sound, written form, and divine power.

Crucially, Odin then bestows this knowledge upon humans, signaling a remarkable aspect of his character: despite his status as a god, he engages with humanity and grants them tools for wisdom, communication, and cultural expression. This generosity underlines his role as Allfather, a figure who nourishes both the material and spiritual life of his people. In Old Norse poetic tradition, he is also called the Alfaeder, a term echoing both “All-Father” and, phonetically, “All-Feeder” — evoking a being who breathes life and wisdom into the world and into humans, linking him to creation itself. Some accounts of Germanic cosmogony depict Odin as instrumental in shaping humanity, further emphasizing this paternal, life-giving aspect.

Odin’s mastery of sound and speech extends beyond the runes themselves. Long before the advent of writing, Germanic peoples transmitted law, lore, and ritual orally, relying on precise pronunciation, rhythm, and mnemonic patterns. By linking runes to speech and song, Odin is portrayed as the guardian of oral tradition, ensuring that knowledge, poetry, and magic persist across generations. This duality — as war-god and wise teacher, as fate-bringer and life-giver — reinforces his status as the Allfather, who mediates between divine insight and human agency.

In this context, Odin’s self-sacrifice, his gift of the runes, and his role as Alfaeder converge: he is a figure of authority, wisdom, and care, whose interventions shape both the destiny of mortals and the spiritual architecture of the world itself. Through the runes, humans are granted the power to name, to create, and to act — a symbolic extension of Odin’s own cosmic intelligence.

Odin in Later Folklore and Cultural Memory

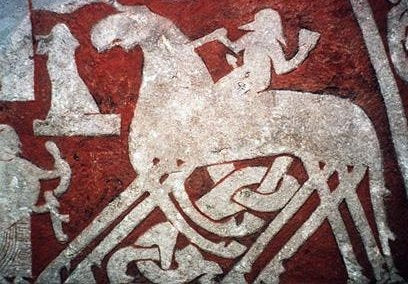

A C-type bracteate (DR BR42) featuring a figure above a horse flanked by a bird, believed to be Odin / Photo: Bloodofox, CC BY-SA 3.0

Even after Christianization, Odin’s presence persisted. The Wild Hunt in German, Scandinavian, and English folklore recalls him as a spectral leader of the dead. In linguistic traces, Wednesday (Wōdnesdæg) commemorates his lasting cultural influence. Folktales in Norway and Iceland preserve his persona as a wandering figure, sometimes named Grímr, emphasizing his continuing relevance in popular imagination.

In modern times, Odin has been reshaped yet again, from Romantic literature to Wagnerian opera, and now in contemporary Heathenry, where he is venerated as Allfather, teacher, and guide. His enduring versatility reflects his historical adaptability and deep resonance with Germanic conceptions of wisdom, power, and destiny.

Odin’s trajectory across Germanic sources demonstrates a deity who is both universally present and endlessly mutable. From Tacitus’ Mercury to the sagas of Snorri and the Poetic Edda, he embodies the full spectrum of Germanic ideals: warrior and poet, seeker of wisdom, manipulator of fate, and patron of kings. He is a figure of paradox: cruel and wise, inspiring and terrifying, human-like and godlike. Odin’s enduring significance lies in his ability to encapsulate the complex worldview of the Germanic peoples, a reflection of their violence, honor, artistry, and longing for understanding in a world governed by fate.

ᚸ

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Was Odin a real historical figure?

While some scholars speculate Odin may reflect a historical chieftain, there is no direct evidence. He is primarily a mythological and literary figure, though he may preserve cultural memory of ancestral leadership.

How did Odin influence kingship among Germanic peoples?

Odin was often cited as ancestor of royal lineages, providing divine legitimacy. In the Ynglinga saga and Anglo-Saxon genealogies, rulers traced their descent from him to justify authority.

What is the relationship between Odin and runes?

According to Hávamál, Odin hung himself on Yggdrasil for nine nights, sacrificing himself to gain knowledge of the runes, linking wisdom, magic, and poetic inspiration.

How did Christianization affect Odin’s cult?

Christian sources often demonized Odin, portraying him as a sorcerer or antagonist to Christ. Pagan practices were outlawed, and some aspects of his persona survived in folklore, such as the Wild Hunt.

Why is Odin so central in Germanic mythology?

Odin represents the archetype of the Allfather: ruler, poet, seer, and war-god. His universality across Germanic tribes reflects a shared cultural ideal of wisdom, courage, and engagement with fate.

References

Tacitus, Germania, c. 98 CE.

Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, 11th c.

Snorri Sturluson, Prose Edda, c. 1220.

Poetic Edda (Codex Regius), c. 1270 (oral tradition).

Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, c. 1200.

Paul the Deacon, Historia Langobardorum, 8th c.

Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North, 1964.

Lindow, John. Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, 2001.

Davidson, H.R. Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, 1964.