Article: The Anglo-Saxon Runes: Language, Lore, and Legacy of the Futhorc

The Anglo-Saxon Runes: Language, Lore, and Legacy of the Futhorc

The runes of the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc represent one of the earliest native scripts of the English-speaking peoples. Evolving from the Elder Futhark of continental Germanic tribes, the Futhorc expanded to reflect the unique phonology of Old English. Beyond serving as a writing system, the runes played roles in ritual, magic, and cultural identity. Though ultimately replaced by the Latin alphabet, they remain historically significant, linguistically revealing, and symbolically rich.

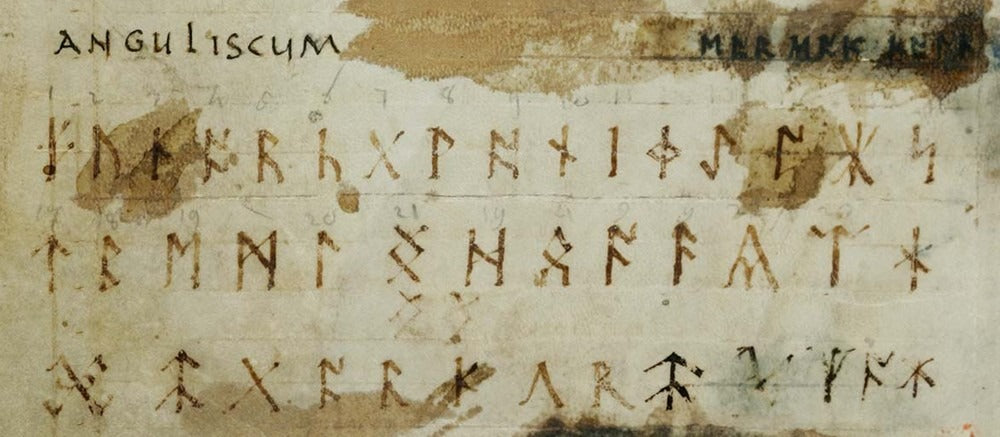

Origins and Development of the Futhorc

The 7th century Franks Casket, as displayed in the British Museum, features the tale of Weyland the Smith and a runic riddle in Anglo-Saxon runes (Photo: Michel Wal CC BY-SA 3.0)

From Elder Futhark to Anglo-Saxon Script

The Elder Futhark, used by Germanic-speaking peoples from the 2nd to 8th centuries CE, consisted of 24 runes. As Germanic tribes migrated to Britain in the 5th century (during the Migration Period) they brought this writing system with them. In Anglo-Saxon England, phonological changes in the developing Old English language required additional symbols, prompting a gradual expansion of the runic inventory. This gave rise to the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, which eventually comprised 28 to 33 characters.

Expansion to Match Old English

Old English developed several vowel sounds and diphthongs absent from Proto-Germanic, necessitating new runes. This adaptation reflects the practical and evolving use of runes as a functional script. It also allowed for clearer representation of native English words, arguably more precise than what the Latin alphabet could offer.

Structure of the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc

The 33 Runes: Names, Phonetics, and Meanings

Each rune in the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc had a name, a phonetic value, and often a symbolic or poetic meaning. As the English language evolved beyond the phonetic needs of the older 24-character Elder Futhark, new runes were created to represent diphthongs and native sounds. Many of these names and associations are preserved in the Old English Rune Poem, a 10th-century work that offers insight into their meanings. Below is a summary of the runes as they were used in Old English writing, along with notes where interpretation remains debated:

ᚠ Feoh (f) – Wealth, cattle; symbol of prosperity and status.

ᚢ Ur (u) – Aurochs; raw strength, primal energy.

ᚦ Þorn (th) – Thorn; danger, defense, or challenge.

ᚩ Ōs (o) – God or mouth; divine speech, inspiration.

ᚱ Rād (r) – Ride or journey; travel, motion, pilgrimage.

ᚳ Cēn (c/k) – Torch; knowledge, fire, enlightenment.

ᚷ Gyfu (g) – Gift; generosity, mutual obligation.

ᚹ ƿynn (w) – Joy; bliss, harmony, delight.

ᚻ Hægl (h) – Hail; natural disruption, transformation.

ᚾ Nȳd (n) – Need; hardship, constraint, necessity.

ᛁ Īs (i) – Ice; stillness, challenge, danger.

ᛄ Gēr (j/y) – Year; harvest, fertility, the turning seasons.

ᛇ Ēoh (eo) – Yew tree; death, endurance, protection. (Some debate over exact sound.)

ᛈ Peorð (p) – Uncertain meaning; possibly dice, fate, or joy in games. Scholarly debate continues.

ᛉ Eolh (x) – Elk-sedge; defense, protection, sharpness.

ᛋ Sigel (s) – Sun; success, light, victory.

ᛏ Tir (t) – Tiw (Týr), the god of justice; law, order, sacrifice.

ᛒ Beorc (b) – Birch tree; birth, fertility, renewal.

ᛖ Eh (e) – Horse; movement, loyalty, cooperation.

ᛗ Mann (m) – Man; humanity, the individual and society.

ᛚ Lagu (l) – Water; flow, life’s journey, instability and guidance.

ᛝ Ing (ng) – Ing (a god); fertility, potential, ancestry.

ᛟ Ēðel (œ/o) – Homeland or inheritance; nobility, ancestral land.

ᛞ Dæg (d) – Day; awakening, clarity, divine light.

ᚫ Æsc (æ) – Ash tree; strength, resilience.

ᛡ Ior (io) – Eel or serpent; adaptability, fluid motion. (Symbolism is still debated.)

ᛠ Ear (ea) – Grave or earth; mortality, decay, finality.

ᛢ Cweorth (?) – Possibly related to ritual fire or cremation; obscure and unattested outside glossaries.

ᛣ Calc (k/ch) – Possibly “chalice”; may be linked to Christian ritual, uncertain.

ᛤ Cealc (k/ch) – Chalk or lime; unclear meaning, possibly related to burial or earth.

ᛥ Stan (st) – Stone; permanence, solidity, enduring truth.

ᛦ Gar (g) – Spear; warfare, divine authority. This rune appears in inscriptions like the Ruthwell Cross.

Though the core runes were used in inscriptions and manuscripts alike, several of the late additions—such as Cweorth, Calc, and Cealc—are known only from medieval manuscripts and may never have been used in daily writing. Some, like Peorð and Ior, remain debated among philologists and runologists. Nevertheless, the Futhorc demonstrates a remarkable adaptability and an enduring cultural framework that matched language, symbolism, and belief into a single writing system.

Runes as Writing and Record

Inscriptions and Manuscripts

The Futhorc was used in a variety of inscriptions—on objects, monuments, and religious items. The Franks Casket, Ruthwell Cross, and Thames scramasax are key archaeological examples. Runic inscriptions were often brief but conveyed identity, dedication, or memory.

In manuscripts, runes occasionally appeared within Latin texts, especially in poetic or cryptic contexts. Scribes used runes like thorn (þ) and wynn (ƿ) for sounds poorly represented by the Roman alphabet.

Comparisons with Latin Script

The Latin alphabet was poorly suited to Old English. Runes like thorn (þ), wynn (ƿ), and eo (ᛇ) represented specific sounds that Latin lacked. In writing unlatinated, native English, runes arguably offered a more efficient and phonologically accurate script. Despite this, Latin script prevailed due to ecclesiastical authority.

Runes in Ritual and Symbol

Silver knife with runic inscriptions, found in the Thames, dating back to the late 8th century (Photo: BabelStone)

Runes were not merely letters but symbols of inherent power. The term rún originally meant "secret" or "whisper." Anglo-Saxon charms sometimes refer to carved letters, and parallels with Norse traditions suggest runes were used in magic—on amulets, swords, or healing objects.

As Christianity spread, runes were adapted rather than immediately rejected. The Old English Rune Poem reflects Christian moral lessons, interpreting rune meanings through a spiritual lens. Syncretism allowed some continuity in usage while transforming the rune's interpretive framework.

Decline and Rediscovery

By the 11th century, the Futhorc had largely fallen out of use, replaced by Latin writing in official and ecclesiastical contexts. However, certain runic letters like thorn and wynn remained in manuscript use into the Middle English period.

The Futhorc resurfaced in early modern antiquarian study and again in modern times through historical, linguistic, and cultural revival. In Anglish movements and Old English study, runes offer a more native system for representing English speech, especially when using pre-Norman vocabulary.

Conclusion: Reclaiming a Native Script

The Anglo-Saxon runes were never merely a set of characters—they were a reflection of early English identity, worldview, and sound. As a writing system, the Futhorc captured the phonological intricacies of Old English more faithfully than the Roman alphabet could. As symbols, each rune carried layered meanings, drawn from myth, nature, and human experience.

Though replaced by the Latin script, the runes did not die. They survive in manuscripts, in heritage objects, and in the very fabric of the English language. For those seeking to reconnect with the roots of English—linguistically, culturally, and spiritually—the Futhorc remains a powerful tool. Its runes still speak, not only from stone and vellum but from the deeper memory of the tongue that shaped them.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many runes are in the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc?

The fully developed Anglo-Saxon Futhorc contains 33 characters, expanded from the 24-character Elder Futhark to match the phonological needs of Old English.

Were Anglo-Saxon runes used for everyday writing?

Yes, though mostly for inscriptions on objects. Manuscripts also include runes, but Latin script became dominant for formal writing after Christianization.

Did the Anglo-Saxons believe runes had magical properties?

Yes. Runes were used in charms and possibly healing rituals. The word rún originally meant "mystery" or "secret", indicating an esoteric role.

Why were runes replaced by Latin letters?

Christian missionaries introduced Latin as the script of the Church. Over time, institutional, religious, and educational pressures led to the adoption of Latin script.

Are Anglo-Saxon runes still used today?

They are no longer used in daily writing but are studied academically and by language revivalists. Some modern Anglish writers use them to represent native English sounds more clearly.

References

Page, R. I. An Introduction to English Runes. Boydell Press, 1999.

Bammesberger, Alfred. The Place of the Anglo-Frisian Runes in the History of the Runic Script. Heidelberg, 1991.

Elliott, Ralph. Runes: An Introduction. Manchester University Press, 1959.

Hough, Carole. The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford University Press, 2016.

North, Richard. Heathen Gods in Old English Literature. Cambridge University Press, 1997.