The Visigoths: Legacy, Law, and Religion in Hispania

The Gothic Homeland and Ethnogenesis

The Visigoths emerged as one of the two primary branches of the Goths, a Germanic people originally from Scandza (Scandinavia), from where they migrated southward over time in different waves. By the second and third centuries CE, the Goths had settled around the Vistula River in what is now modern-day Poland before moving further south into the forested and steppe regions north of the Black Sea, commonly referred to as Scythia. It was in this area that the Gothic people began to distinguish themselves in historical records. The division between the Tervings and Greuthungs—terms believed to mean “forest dwellers” and “steppe dwellers” respectively—reflected their geographic and environmental differences, with the Tervings inhabiting wooded areas west of the Dniester River and the Greuthungs occupying the open steppe lands to the east. This distinction was first recorded by Roman historians such as Ammianus Marcellinus and later formalized by Jordanes in the sixth century CE in his Getica, where the terms correspond broadly to the later Visigoths (Tervings) and Ostrogoths (Greuthungs).

Contact with Rome and Migration Period Dynamics

By the third century, Gothic raids across the Danube began to pressure the Roman Empire. These raids intensified in the wake of political instability in Rome and external pressures on the Gothic world from the Huns. In 376 CE, the Tervings, under the leadership of Fritigern, sought asylum within the Roman Empire to escape the advancing Huns. This marked a key moment in the Migration Period, as Rome struggled to manage the influx of non-Roman peoples into its territories.

The Visigoths and the Western Roman Empire

"The Plunder of Rome" Painting by Joseph-Noel Silvestre

The Battle of Adrianople and Its Aftermath (378 CE)

Denied fair treatment and adequate supplies by Roman officials, the Tervings revolted. In 378 CE, they decisively defeated the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople, killing Emperor Valens. This battle profoundly shook the Roman world, demonstrating the military prowess of the Visigoths and exposing the empire's inability to manage its frontiers.

Alaric and the Sack of Rome (410 CE)

Under Alaric I, the Visigoths became a roaming, powerful military force within Roman borders. Despite being appointed magister militum by the Romans, Alaric's demands for land and recognition were unmet. In 410 CE, he led the Visigoths in the sack of Rome, a symbolic moment signalling the decline of Roman power in the West. Alaric died shortly afterward, but his successors continued the westward migration.

Settlement in Gaul and Transition into Hispania

Under King Wallia and later Theodoric I, the Visigoths were settled as foederati in Aquitaine around 418 CE. From this base in southwestern Gaul, they expanded into Hispania, gradually displacing the Vandals, Alans, and Suebi. By the mid-fifth century, the Visigoths had established a permanent kingdom encompassing much of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania

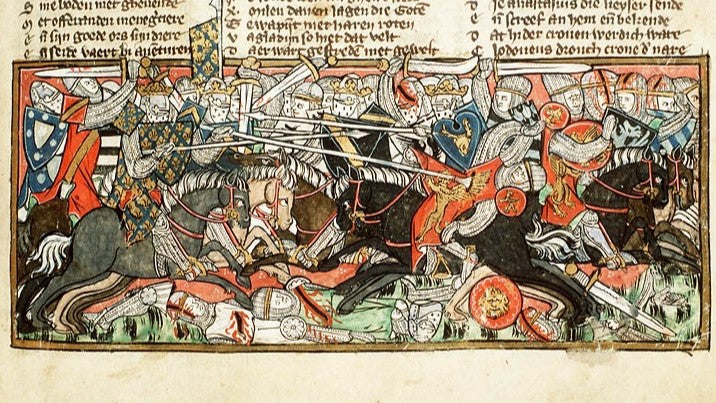

Illustration from Lámina 2 of El Álbum de la caballería española, published under the direction of José Marchesí. According to the Count of Clonard, Gothic kings maintained a royal cavalry guard for their protection.

Early Rule and Conflicts with the Suebi and Vandals

Visigothic expansion into Hispania brought them into direct conflict with the Suebi, who controlled parts of northwestern Iberia. The Visigoths waged intermittent wars until the Suebi were ultimately defeated and annexed in the mid-sixth century. Earlier, they had also contested territory with the Vandals and Alans, who eventually crossed into North Africa.

The Reign of Leovigild and Religious Consolidation

Leovigild (r. 568–586 CE) is often regarded as one of the most powerful Visigothic rulers. He unified much of the peninsula and sought to strengthen central authority. A major internal challenge was the religious divide between Arian Visigoths and Nicene (Catholic) Hispano-Romans. Leovigild tried to impose Arianism but faced resistance. His son, Reccared I, converted to Catholicism in 587 CE, effectively ending the schism and fostering greater unity.

Coin depicting Liuvigild (568–586) of Visigothic Kingdom (Photo: Classical Numismatic Group CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Councils of Toledo and Integration Policies

The Visigothic Kingdom became increasingly Romanized, using Latin in administration and codifying law through the Lex Visigothorum. The Councils of Toledo, particularly the Fourth (633 CE), played a central role in shaping religious and political policy. These councils strengthened the power of the Catholic Church and institutionalized cooperation between church and monarchy.

Decline and the Umayyad Conquest (711 CE)

In the early 8th century, internal dynastic struggles weakened the Visigothic state. In 711 CE, the forces of Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād, under the Umayyad Caliphate, invaded Hispania. The Visigothic king Roderic was defeated at the Battle of Guadalete, leading to the rapid collapse of the kingdom and the Islamic conquest of Iberia.

Visigoths vs. Ostrogoths: Diverging Paths

Differences in Settlement and Political Structure

While the Visigoths established a lasting kingdom in Hispania, the Ostrogoths, under Theodoric the Great, carved out a realm in Italy following the deposition of the last Western Roman Emperor in 476 CE. The Ostrogothic Kingdom emphasized continuity with Roman institutions, maintaining senatorial structures and cooperating with the Eastern Roman Empire, at least nominally.

Distinct Relations with Rome and Byzantium

The Visigoths had a more antagonistic relationship with the Western Roman Empire, particularly during the sack of Rome. In contrast, the Ostrogoths presented themselves as restorers of Roman order. However, the Eastern Empire later sought to eliminate Gothic rule in Italy, launching the Gothic War (535–554 CE), which ultimately ended Ostrogothic autonomy.

Shared Gothic Identity and Conflicting Interests

The Lombards, another Germanic group, settled in Italy after the fall of the Ostrogoths. While sharing certain cultural affinities with the Goths, including Germanic law and warrior traditions, they often clashed with remnants of Gothic nobility and had limited interaction with the Visigoths, whose domain lay further west. The Lombards did, however, inherit many of the administrative structures left by the Goths in Italy.

The Visigoths in Jordanes' Getica

Historical Role and Mythical Elements

Jordanes’ sixth-century Getica provides a semi-legendary account of Gothic history, drawing on earlier works such as Cassiodorus. He traces the origins of the Goths to Scandinavia and describes their migration and exploits across Europe. The Visigoths are portrayed as a powerful and noble people, distinct from the Ostrogoths but equally central to the Gothic legacy. Although some claims in Getica are considered mythologized, it remains a crucial source for understanding Gothic self-perception and historical narrative.

Conclusion: The Visigothic Legacy

The Visigoths played a pivotal role in the transformation of the Western Roman world. From their emergence as Terving migrants fleeing the Huns to the creation of a powerful kingdom in Hispania, their history reflects the larger narrative of the Migration Period. Unlike the Ostrogoths, their kingdom endured for centuries, shaping Iberian religion, law, and identity. Their legacy continued in the cultural memory of Spain, where Visigothic law codes and church structures influenced both Christian and Islamic periods that followed.

ᚸ

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What was the main difference between Visigoths and Ostrogoths?

The Visigoths settled in Hispania and had an antagonistic relationship with the Western Roman Empire, while the Ostrogoths ruled Italy and initially cooperated with the Eastern Empire.

Did the Visigoths sack Rome?

Yes, under Alaric I, the Visigoths famously sacked Rome in 410 CE after failed negotiations with the Western Roman authorities.

Who was the most important Visigothic king?

Leovigild is often seen as the most powerful ruler due to his consolidation of territory and central authority. His son Reccared I played a key role in religious unification.

How did the Visigothic Kingdom fall?

It collapsed after the Muslim invasion of 711 CE, following years of internal strife and weakened royal authority.

Are the Visigoths mentioned in the Getica?

Yes, Jordanes' Getica includes a detailed account of Visigothic origins, migration, and distinction from the Ostrogoths.

References

Heather, Peter. The Goths. Wiley-Blackwell, 1996.

Wolfram, Herwig. History of the Goths. University of California Press, 1988.

Jordanes. Getica. Translated by Charles Mierow.

Kulikowski, Michael. Rome's Gothic Wars. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Thompson, E.A. The Visigoths in the Time of Ulfila. Clarendon Press, 1966.