The Rise and Fall of Burgundy: History, Law, and Legacy

The Burgundians were a Germanic people whose origins, according to classical and early medieval sources, lay in the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea—referred to in Latin as Burgundarholm. Their migration southward is part of the broader Germanic migrations that reshaped Europe in late antiquity. As with other groups such as the Goths, some sources, like Jordanes, suggest a Scandinavian point of origin, though archaeological evidence is less definitive.

By the late third century CE, the Burgundians began to appear in Roman records along the Vistula River, in what is now Poland. From there, they migrated westward across the Rhine, interacting with Roman frontiers and other Germanic tribes. Their movements were likely influenced by both push factors, such as pressure from Hunnic expansions, and pull factors, such as the weakening of Roman control and the promise of settlement within the Empire.

Settlement on the Roman Frontier

Kingdom of the Burgundians, after the settlement in Eastern Gaul from 443 (Photo: Marco Zanoli CC BY-SA 4.0).

By the early fifth century, the Burgundians had settled on the western bank of the Rhine, in the region around Worms. In 406 CE, amid a major wave of barbarian incursions across the Rhine, the Burgundians were among those who crossed into Roman Gaul. Their presence became increasingly formalized when the Roman general Flavius Aëtius granted them foederati status—meaning they were settled within the Empire as allies obligated to supply military support.

This initial settlement was short-lived. In 436 CE, the Burgundians, under their king Gundahar (later rendered Gunther in legend), were devastated by a Roman-Hunnic coalition army. The Roman Empire, threatened by the Burgundians' expansionist behavior, reportedly enlisted Hunnic auxiliaries under Attila to suppress them. The capital at Worms was destroyed, and much of the royal family was killed.

Formation of the Second Kingdom of Burgundy

Location of Burgundy in France (Photo: TUBS CC BY-SA 3.0).

Following this destruction, Aëtius resettled the surviving Burgundians in the western Alps, in the region known as Sapaudia (modern-day Savoy and parts of the Rhône Valley). Here, they founded a new kingdom under King Gundioc, a brother or relative of Gundahar. This Second Kingdom of Burgundy, with Lyon and Geneva as major centers, gradually expanded into Roman southeastern Gaul during the late fifth century.

The Burgundians adopted many elements of Roman administration and law. They issued the Lex Burgundionum under King Gundobad in the early sixth century, which served as a written law code blending Roman legal principles with Germanic custom. Notably, Gundobad himself had served briefly as magister militum and even held imperial power in Italy before returning to Burgundy.

The Burgundian kingdom became increasingly Romanized over time. Latin was used in administration, and Christianity—initially in its Arian form—eventually transitioned to Nicene orthodoxy by the end of the sixth century.

Absorption by the Merovingian Franks

The independence of the Burgundian kingdom ended during the reign of the Merovingian Franks. Clovis I, the first Christian king of the Franks, campaigned against Burgundy during the early sixth century. A protracted conflict unfolded between Clovis’ heirs and the Burgundian kings Sigismund and his brother Godomar.

In 523 CE, Sigismund was captured and executed by Clovis’ son Chlodomer. Though Godomar attempted to rally the kingdom, the final defeat came at the Battle of Autun in 532 CE. Burgundy was subsequently annexed by the Franks in 534 CE and incorporated into the growing Merovingian realm. Nevertheless, its regional identity persisted, and it later re-emerged as a territorial unit in the Carolingian Empire.

Legacy in Law, Language, and Identity

Gold Burgundian necklace found at Wrocław - Rędzin (Photo: Silar CC BY-SA 4.0).

Despite their absorption, the Burgundians left a deep imprint on the region of southeastern Gaul. The Lex Burgundionum continued to be used for decades under Frankish rule, particularly for cases involving Burgundian subjects. Over time, intermarriage and cultural blending erased the distinction between Burgundians and other Gallo-Roman or Frankish populations.

Place names and regional identities retained the memory of the Burgundians. The name "Burgundy" endured and became associated with a powerful duchy in the Middle Ages and later a kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire. Though distinct from the early Burgundian polity, these later Burgundies drew symbolic legitimacy from the earlier kingdom.

The Burgundians in Myth: The Nibelungenlied and Beyond

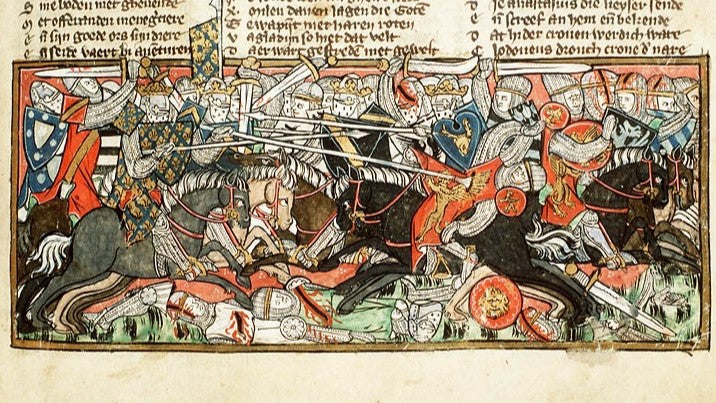

While historical records chart the rise and fall of the Burgundians, their memory lived on in medieval epic. The Nibelungenlied, a High German epic from around the 13th century, immortalized characters based on Burgundian royalty. Gunther (from King Gundahar), Hagen, and others feature prominently in this mythologized retelling, alongside Siegfried and Brunhild.

Set primarily in Worms, the Nibelungenlied portrays the downfall of the Burgundians in heroic terms, echoing the historical catastrophe of 436 CE. Hagen’s betrayal of Siegfried and the final massacre of the Burgundians at the court of Etzel (Attila) retain a shadow of historical memory, even if transformed by legend.

The blending of historical figures and mythic drama in such literature reflects how the Burgundians straddled two worlds: one rooted in the factual migrations and wars of late antiquity, and another embedded in the cultural imagination of medieval Europe.

Conclusion: A People Between History and Legend

The Burgundians were one of the many Germanic tribes that migrated into the Roman world during its final centuries. From a likely northern homeland, they journeyed into the heart of Gaul, founded kingdoms, fought with and against Rome, and left behind laws and legacies that outlasted their political independence. Their memory endured not just through legal codes or Frankish absorption, but through epic poetry that immortalized their kings in the mythic consciousness of Europe.

As with the Goths and Vandals, the Burgundians reflect the complexities of the so-called “barbarian invasions”—not merely destroyers of Rome, but participants in a new cultural and political order that shaped medieval Europe. Their story is one of transformation, from migrants to monarchs, from warriors to legend.

ᚸ

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Where did the Burgundians originally come from?

Classical sources place their origin on the island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea. They later migrated through the Vistula region and into Roman Gaul.

What happened to the original Burgundian kingdom at Worms?

It was destroyed in 436 CE by a Roman-Hunnic army. Many Burgundians, including King Gundahar, were killed.

How did the Burgundians become part of the Frankish realm?

After a series of conflicts in the early sixth century, Burgundy was annexed by the Merovingian Franks in 534 CE.

What is the Lex Burgundionum?

It was a legal code issued under King Gundobad that blended Roman and Germanic law, used primarily for cases involving Burgundian subjects.

Who are the Burgundians in the Nibelungenlied?

They are mythologized as heroic figures, with characters like King Gunther and Hagen inspired by historical Burgundian leaders.

References

Heather, Peter. The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Halsall, Guy. Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Jordanes. Getica. Translated by Charles Mierow.

Wolfram, Herwig. History of the Goths. University of California Press, 1988.

Goffart, Walter. Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Wood, Ian. The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450–751. Routledge, 1994.