Who is Fenrir in Norse Mythology? Unraveling the Origins, Binding, and Fate of the Chaotic God of Destruction

Within the labyrinthine lore of Norse mythology, Fenrisúlfr (also known as Hróðvitnir, Vánagandr, Fenrir or Fenrirs) emerges as a pivotal figure, his story interwoven with threads of prophecy, divine machination, and scholarly inquiry. Born of the union between the trickster Loki and the enigmatic giantess Angrboða, Fenrir's existence was marked by ominous portents, his fate entwined with the impending Twilight of the Gods, Ragnarök. Alongside his siblings, Jormungandr and Hel, Fenrir traverses a narrative landscape that spans from the hallowed halls of Asgard to the shadowed realms of the underworld. Yet, beyond the mythic contours of his tale lies a rich tapestry of historical evolution, scholarly discourse, and artistic interpretation, each layer adding depth to the enigma of Fenrir and his significance within the pantheon of Norse deities. As we delve into the binding of Fenrir, we embark on a journey that traverses not only the realms of gods and giants but also the annals of human imagination and inquiry.

The Binding of Fenrir:

Fenrir Being Bound by the Aesir Gods, by Dorothy Hearthy 1909 (Public Domain)

Fenrir’s tale begins in this prose narrative that tells the story Fenrir's birth and binding. Born to the trickster god Loki and the giantess Angrboða, Fenrir was fated by the Norns to play a terrible role in Ragnarök, as acclaimed by the Völva. Alongside Fenrir, was Jormungandr, (the Midagard Serpent) and Hel, the goddess of death. Jormungandr was cast into the Earth’s Sea by Odin – the Allfather may have done this in hopes the serpent would drown and die, or merely to move him far away from Asgard. Either way, Fenrir’s serpent brother would grow to a monstrous size, eventually growing so large he overlapped all across Midgard, biting down onto his own tale. Hel was cast away to the underworld who shared her name, Hel.

Loki's brood; Hel, Fenrir and Jörmungandr. The figure in the background is presumably Angrboða. (Public Domain)

Fenrir on the other hand was kept closer to the gods then his siblings. For a time, he was reared by the Aesir in Asgard. He was fed by the only god who dared approach the monstrous wolf – Tyr, the god of law, honour, justice, and war. But Fenrir grew at an alarming rate, and soon the gods decided that his stay in Asgard had to be temporary. The gods attempted to bind Fenrir with various chains, telling him that these fetters were tests of his strength. Each time, Fenrir broke free, to the gods’ applause. Finally, the gods sent a messenger to Svartalfheim, the realm of the dwarves. The dwarves, skilled craftspeople, forged an unbreakable chain named Gleipnir. It was made from the sound of a cat’s footsteps, the beard of a woman, the roots of mountains, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird - things which don’t exist, and against which it’s therefore futile to struggle.

A 17th-century manuscript illustration of the bound Fenrir, the river Ván flowing from his jaws (Public Domain)

When the gods presented Fenrir with Gleipnir, the wolf suspected trickery and refused to be bound with it unless one of the gods would lay his or her hand in his jaws as a pledge of good faith. None of the gods agreed, knowing that this would mean the loss of a hand and the breaking of an oath. At last, the brave and honourable Tyr volunteered to fulfill the wolf’s demand. And, sure enough, when Fenrir discovered that he was unable to escape from Gleipnir, he chomped off and swallowed Tyr’s hand. The fettered beast was then transported to the island of Lyngvi. The chain was tied to a boulder and a sword was placed in the wolf’s jaws to hold them open. As he howled wildly and ceaselessly, a foamy river called “Expectation” (Old Norse Ván) flowed from his drooling mouth, hence his other name 'Vánagandr' (meaning 'Monster of the [River] Ván' in Old Norse). And there, in that sordid state, he remained – until Ragnarok.

Völuspá:

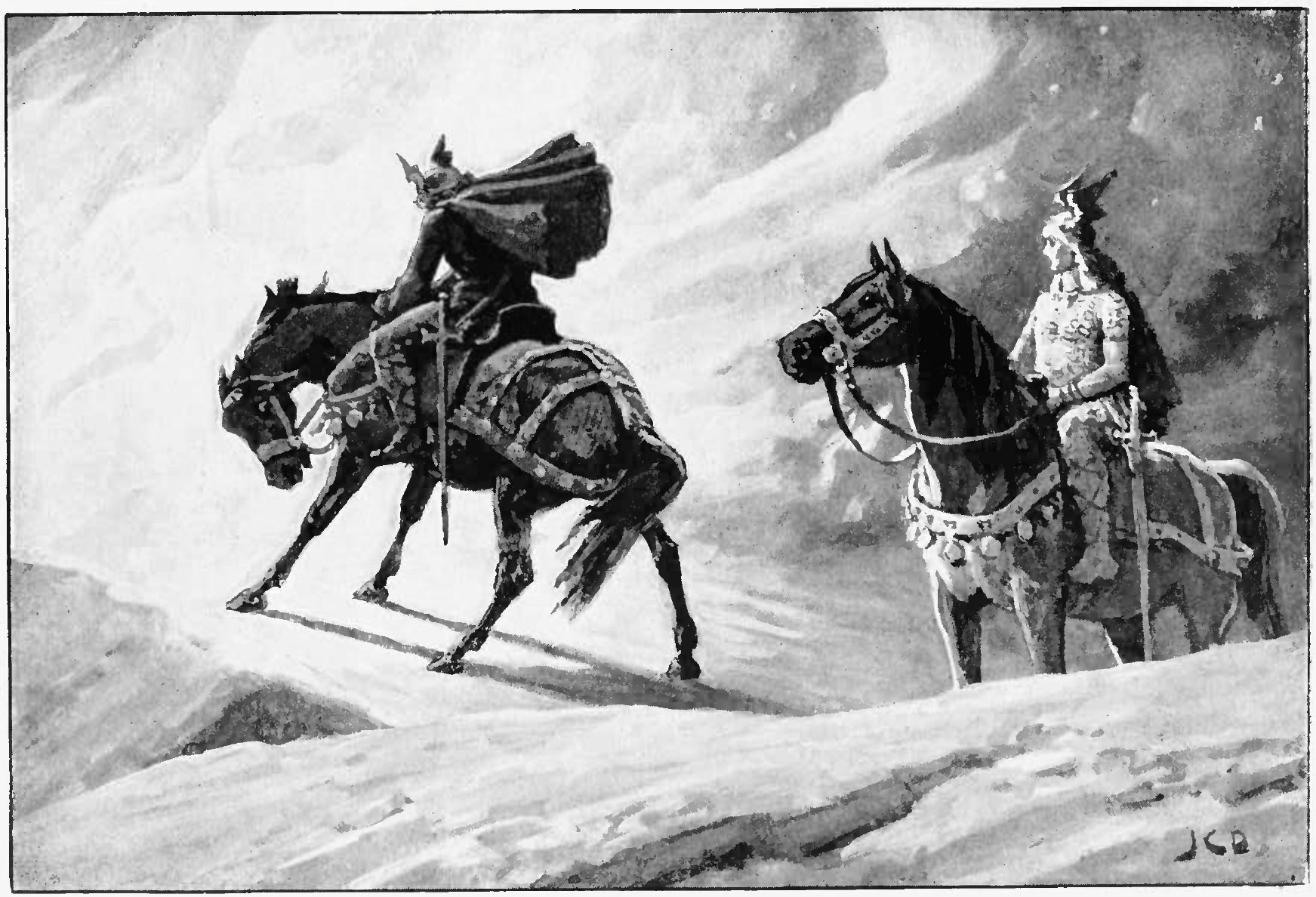

Odin and Fenris wolf, Freyr and Surt (1905) by Emil Doepler

In the poem of Völuspá, meaning ‘Prophecy of the Völva’, Odin reanimates a Seeress in search of more knowledge, more specially future events. She reveals to Odin that an old woman in the east forest of Járnviðr bred the broods of Fenrir. It tells the story of the beginning and end of the world, including the events of Ragnarök. As Ragnarök approaches, Fenrir breaks free from his bonds. His lower jaw against the ground and his upper jaw in the sky, he runs throughout the world, devouring everything in his path. This includes the sun and the moon (in some versions) plunging the world into darkness. The horn of Heimdall announces the final battle. The giants, including Fenrir, come together for this voyage, with Loki as their captain. The gods, the Aesir, are in counsel, and all Jotunheim, the world of the giants, is roaring. Odin, the Allfather, goes to fight Fenrir, fulfilling the second sorrow of Frigg, Odin’s wife. In this battle, Odin falls to Fenrir.

Víðarr slaying Fenrir (1908) by W. G. Collingwood (Public Domain)

Then comes Víðarr, the great son of Odin, to fight Fenrir and avenge his father. He shoves his sword into the mouth of Fenrir, all the way to the heart, and thus avenges Odin. This prophecy, as told by the völva, reveals the dark future of the gods and the world. Despite Odin’s efforts to change this fate, his actions only lead him closer to these final outcomes – such as how they treated Fenrir and his siblings. Fearing what this monstrous spawn of Loki would do, the gods attempt to stop it before it even begins, but this merely starts the long and deep resentment against the Aesir and in turn causes their destruction.

Historical Evolution:

Fenrir and Naglfar on the Tullstorp Runestone

Fenrisúlfr has been interpreted in many depictions in forms of art and literature throughout his long history, including (but not limited to), medieval manuscripts, runestones and carvings, Renaissance art, 19th century Romanticism and modern fantasy art and has grown to be one of the most popular and renowned figures in Old Norse mythology.

As a historical deity, Fenrir has a rich and long history that traces back to early Germanic Mythology before the settling of Scandinavia. Over time, he has grown from a simple monstrous wolf from his Germanic roots to a much more in-depth and complex character in Norse Mythology. His significant role in Norse Mythology, responsible for the death of Odin and one of the primary bringers of Ragnarok, reflects the evolution of Germanic mythos into its Norse counterpart, with its richly detailed cosmology and complex network of all the gods, giants, creatures, and other creatures in the poems.

An illustration of an image on a bracteate found in Trollhättan, Västergötland, Sweden. The image is considered as a depiction of Týr tricking Fenrir. Drawing by Gunnar Creutz.

Amongst all his appearances in the Eddic Poems, several scholarly theories have been proposed regarding his relations with the numerous other canine characters in the mythology. Particular his two sons, Sköll and Hati. Some theories suggest that most, if not all, wolves mentioned in Norse Mythology were originally Fenrir, while others maintain that Fenrir, Sköll, and Hati are distinct entities with their own roles. This theory no doubt originates from differing versions that speak about Ragnarok. Sköll and Hati, in most versions, are the acclaimed wolves who are in constant pursuit of Sol and Mani, the personified gods of the sun and moon. It is said during Ragnarok, these two wolves will at last catch up and devour them, bringing darkness to the world and possibly being the cause of Fimbulvetr. However, there are other versions of this story where it is Fenrir, who, after at last breaking the chains of Gleipnir, runs across the realms with his mouth still gaped open, devouring everything that stands in his way including the moon and sun. It is theorised by some this was the original version of the story, and the presence of Sköll and Hati came along later down the track to add complexity to the story.

Hel and the Hound Garmr (1889) by Johannes Gehrts. (Public Domain)

In addition to Fenrir, Garmr is another significant canine figure in Norse mythology. Garmr, often depicted as a wolf or dog, is associated with both Hel and Ragnarök, and is described as a blood-stained guardian of Hel’s gate and plays a vital role in the cataclysmic events of Ragnarök. He is described as being bound in chain within the realm of Hel, eerily similar to that of Fenrir being bound up by Gleipnir. Garmr’s possible relation to Fenrir further emphasizes his significance in Norse mythology. It has been suggested that Garmr could be the unnamed dog mentioned in the Baldrs Draumar poem, barking at Odin as he voyages to the underworld. Additionally, Garmr’s connection with the god Tyr is particularly noteworthy, as they are destined to face each other in battle during Ragnarök. This is in fact one of the most prominent points brought up when it comes to this discussion. If it was Fenrir in Garmr’s place, it would be all too poetic for the wolf and Tyr to have one last clash after their long history together.

Conclusion:

The saga of Fenrir serves as a nexus point where myth, history, and interpretation converge. As we navigate the intricate layers of his tale, from the binding fetters of Gleipnir to the foreboding prophecies of Ragnarök, we are drawn into a realm where gods clash, giants loom, and destiny hangs in the balance. Yet, Fenrir's story extends beyond mere mythic narrative, resonating through the annals of art, literature, and scholarly discourse. From medieval manuscripts to modern fantasy realms, Fenrir's shadow stretches across the expanse of human imagination, a testament to the enduring power of myth to captivate and inspire. As we bid farewell to Fenrir, bound yet indomitable, we are reminded that within the echoes of his howls lies not only the promise of cataclysmic doom, but also the inevitable rebirth of the world following its destruction. Fenrir’s story, if anything, tells a tale of how in a time where there is utter chaos and darkness, sometimes those very things are a necessity to bring about a better world and age.