Scythian-Slavic Relations: Conflict and Coexistence on the Eurasian Steppe

The vast expanses of the Eurasian steppe served as the backdrop for centuries of complex interactions between nomadic Scythian tribes and early Slavic peoples. From approximately the 7th century BCE to the 3rd century CE, these distinct cultural groups engaged in relationships characterized by both fierce conflict and pragmatic coexistence. While modern scholarship has increasingly nuanced our understanding of these historical interactions, evidence of military confrontations, cultural exchange, and territorial disputes remains central to understanding this critical period in Eastern European history.

Background of the Scythian and Slavic Peoples

Golden decorative plate shaped like a stag from a Scythian shield (Photo: Joanbanjo CC BY-SA 4.0)

Origins of the Scythians

The Scythians emerged as a formidable presence on the Eurasian steppe around the 7th century BCE. An Iranian-speaking nomadic people, they developed a distinctive culture characterized by exceptional horsemanship, sophisticated metallurgy, and a unique artistic style known as "animal art." Their heartland encompassed the Pontic-Caspian steppe, stretching from the northern Black Sea region across southern Ukraine and into southern Russia, though their influence extended much further through trade networks and military campaigns.

Greek historian Herodotus provided some of the earliest detailed accounts of Scythian society in his 5th century BCE work "Histories," describing their nomadic lifestyle, military prowess, and social customs. Archaeological evidence has substantiated many of these descriptions, revealing a society whose economy centered on pastoralism, with horse breeding as a particularly vital component. Their military might stemmed from their mastery of mounted archery, a tactical advantage that allowed them to dominate large swathes of territory and repel invasions by formidable powers like the Persian Empire under Darius I in 513 BCE.

Early Slavic Societies

The early Slavs present a more challenging historical subject, as they left fewer written records and emerged into historical documentation significantly later than the Scythians. Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that proto-Slavic communities began developing distinctive cultural characteristics around the 5th century BCE in areas of Eastern Europe spanning from the Pripet Marshes to the upper Dniester and Vistula river basins. Unlike the predominantly nomadic Scythians, early Slavic societies were primarily sedentary agriculturalists who established permanent settlements in forested regions, practicing mixed farming and animal husbandry.

The earliest reliable historical mentions of Slavic peoples appear in 6th century CE Byzantine sources, including Procopius and Jordanes, who describe them as "Sclaveni" or "Veneti." However, archaeological evidence indicates that proto-Slavic cultures existed much earlier, with distinctive pottery styles and settlement patterns identifiable from at least the early first millennium BCE. These communities gradually expanded from their initial heartland, eventually spreading across Eastern Europe and interacting with various peoples, including the Scythians along their southeastern frontier.

Geographical Overlap and Territorial Relations

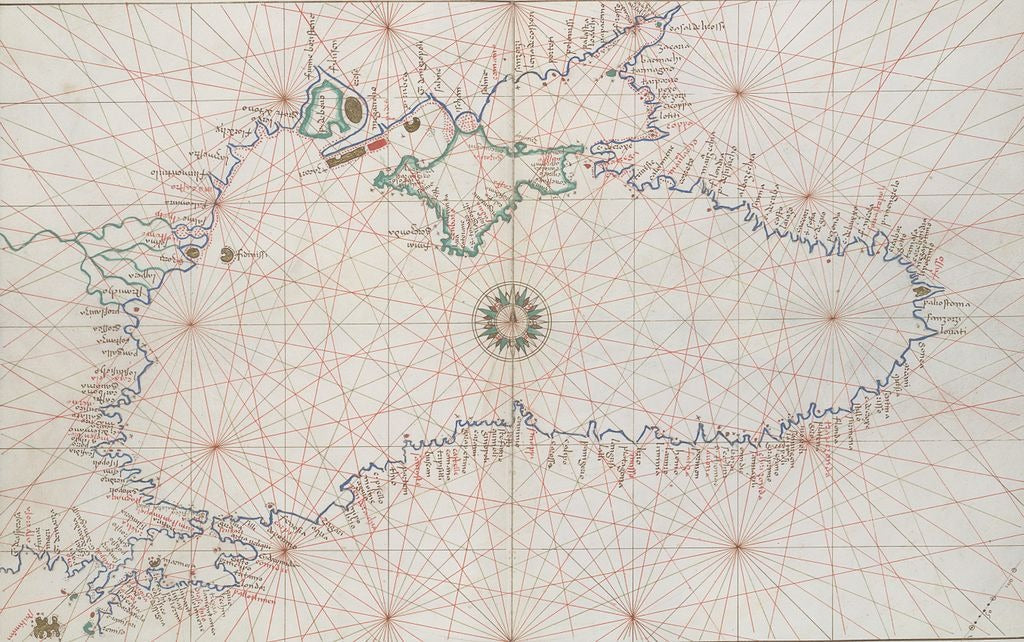

The maximum extent of the Scythian kingdom in the Pontic steppe (Illustration: Antiquistik CC BY-SA 4.0)

Steppe Borderlands

The primary zone of interaction between Scythians and early Slavic peoples occurred along the forest-steppe ecological transition zone stretching from modern Ukraine through southern Russia. This environmental boundary, where the open grasslands of the steppe meet the northern forests, created a natural frontier between the predominantly nomadic Scythian realm and the more sedentary, agricultural Slavic settlements. Archaeological evidence indicates that this border zone was not a sharp line but rather a permeable frontier where populations mixed and influences flowed in both directions.

Key contact regions included the middle Dnieper River basin, particularly around modern Kyiv, and the territories between the Dniester and Dnieper rivers. These areas featured a patchwork of settlements with varying degrees of Scythian and Slavic cultural elements. The strategic importance of these regions stemmed from their role as corridors for trade, migration, and military campaigns, making control of these territories a frequent source of conflict.

Resource Competition

Competition for resources drove many of the tensions between Scythians and early Slavic communities. The Scythians, as nomadic pastoralists, required extensive grasslands for their herds of horses, sheep, and cattle, while Slavic agriculturalists cleared forest land for cultivation. This fundamental difference in economic orientation created inherent tensions over land use, particularly in transitional ecological zones suitable for both lifestyles.

Trade routes represented another critical resource that provoked competition. The Dnieper, Dniester, and Don rivers served as vital arteries for commerce linking the Black Sea with northern territories. Control of these waterways and the portage routes between them offered significant economic advantages, providing access to valuable goods including furs, amber, honey, wax, and slaves from the north, and wine, olive oil, luxury textiles, and metalwork from Mediterranean civilizations. Archaeological evidence from settlements along these routes reveals the material wealth that could be accumulated by those who controlled these commercial pathways.

Military Encounters and Conflicts

Triquetra Mjölnir - Gold & Silver Nordic Urnes Art Engraved Thor's Hammer

Early Confrontations

The earliest well-documented confrontations between Scythians and proto-Slavic peoples likely occurred during the period of maximum Scythian expansion in the 6th-5th centuries BCE. As Scythian power reached its apex under King Idanthyrsus and his successors, their territorial ambitions brought them into more frequent contact with settled populations to their north and west. Archaeological evidence from this period shows an increase in fortified settlements in border regions, suggesting heightened military tensions.

Written sources specifically documenting these early conflicts remain sparse. Herodotus makes only passing references to peoples north of Scythia whom scholars have sometimes identified as potentially proto-Slavic, referring to them as "Neuri" and "Budini." He notes that these groups had distinct customs from the Scythians but provides little detail about the nature of their interactions. Archaeological evidence, however, reveals a pattern of destruction layers at some settlements in the forest-steppe zone during this period, potentially indicating Scythian raids or more sustained military campaigns.

Major Conflicts

The 4th-3rd centuries BCE marked a period of intensified conflict as Scythian power structures faced mounting pressures. With the rise of Sarmatian tribes to their east and the expansion of Celtic and Thracian peoples to their west, Scythian groups increasingly pushed northward into territories inhabited by proto-Slavic peoples. The archaeological record shows evidence of violent destruction at numerous settlements in the middle Dnieper region dating to this period.

One of the most significant documented confrontations occurred around 339 BCE when the Scythian king Ateas attempted to expand his influence northward before his eventual defeat by Philip II of Macedon. Though Greek sources focus primarily on the Macedonian-Scythian conflict, archaeological evidence suggests that this period of Scythian military activity also impacted proto-Slavic communities in the forest-steppe zone, with several settlements showing signs of destruction and hasty abandonment.

By the 2nd century BCE, the balance of power began shifting significantly. The Sarmatians had displaced many Scythian groups from their eastern territories, pushing them further into areas of proto-Slavic settlement. This created a complex three-way conflict dynamic, with displaced Scythian groups frequently raiding Slavic agricultural communities while themselves facing pressure from Sarmatian forces. The archaeological record from this period shows increasing militarization of settlements throughout the region, with more substantial fortifications and higher frequencies of weapons in burial contexts.

Military Tactics and Technology

The military encounters between Scythians and early Slavic peoples featured a stark contrast in tactical approaches and combat technologies. Scythian warfare centered on highly mobile cavalry forces, particularly mounted archers. This allowed them to execute rapid raids, employ hit-and-run tactics, and engage in devastating feigned retreats that lured opponents into ambushes. Their composite bows, capable of penetrating armor at surprising distances, gave them a significant advantage in open-field engagements.

Archaeological evidence indicates that early Slavic military organization emphasized infantry forces and defensive fortifications. The remains of wooden palisades, earthen ramparts, and defensive ditches around settlements suggest a strategy focused on protecting agricultural resources and civilian populations. Slavic warriors typically fought with spears, axes, and simple bows, supplemented in later periods with limited cavalry forces that never matched Scythian mobility or horsemanship.

This tactical disparity shaped the nature of conflicts between the two groups. Scythian forces excelled in open terrain where their mobility provided decisive advantages, while Slavic defenders held stronger positions in forested regions and fortified settlements. Over time, evidence suggests that Slavic communities adapted to the Scythian threat by adopting aspects of steppe military technology, particularly improved bow designs and cavalry tactics, though they never fully embraced the nomadic military system.

Cultural Exchange and Influence

Scythian bronze arrowheads, c700-300 BC (Photo: Bruce C. Cooper CC BY-SA 4.0)

Trade Relations

Despite recurring conflicts, commercial interactions between Scythians and Slavic communities played an important role in their relationship. Archaeological evidence indicates the existence of established trade networks connecting these societies, with certain settlements functioning as trading posts or market centers at the ecological boundary between forest and steppe. These commercial exchanges were typically conducted on a small scale, involving direct barter or exchange facilitated by intermediaries in border regions.

Slavic communities provided agricultural products, forest resources such as fur, honey, wax, and amber, and specialized craft goods to Scythian traders. In return, they received metals (particularly bronze and iron), salt, leather goods, and occasionally luxury items from more distant civilizations that had reached Scythia through Black Sea trade networks. Artifacts found in proto-Slavic settlements include distinctive Scythian bronze works, jewelry, and decorative elements, indicating that luxury goods did penetrate northern communities, likely as prestige items for elites.

Particularly important trading centers emerged at natural geographic junctions, such as river confluences and portage points between watersheds. Archaeological excavations at sites like Bilsk (potentially ancient Gelonus mentioned by Herodotus) in Ukraine reveal evidence of both Scythian and proto-Slavic material culture, suggesting these served as multicultural trading hubs where both groups interacted relatively peacefully despite broader tensions.

Cultural Borrowing

The prolonged contact between Scythian and proto-Slavic societies inevitably led to cultural exchange. Archaeological evidence reveals that proto-Slavic communities adopted elements of Scythian material culture, particularly metalworking techniques and decorative motifs. Artifacts from forest-steppe settlements show increasing incorporation of animal imagery characteristic of Scythian art, though typically adapted to local aesthetic preferences rather than directly copied.

Linguistic evidence suggests some technological borrowing as well. Certain terms in Slavic languages related to metal objects, horse gear, and weapons show possible Iranian (Scythian) origins, though the exact pathways of transmission remain debated among linguists. The adoption of more advanced horse breeding and riding techniques by some Slavic groups also appears to reflect Scythian influence, particularly in frontier communities that faced more frequent Scythian contact.

Conversely, as some Scythian groups began settling in more permanent locations during their period of decline, they adopted agricultural practices and settlement patterns more characteristic of their Slavic neighbors. This process of mutual influence accelerated during the later periods of Scythian history, particularly in the 2nd-1st centuries BCE, as the traditional nomadic lifestyle came under increasing pressure from multiple directions.

The Decline of Scythian Power

Old Norse Amulet Pendant with Elder Futhark Runes – Jelling & Mammen Style

Slavic Expansion

The 2nd century BCE through the 1st century CE witnessed the gradual collapse of Scythian political dominance in the Pontic steppe region. As Sarmatian pressure from the east intensified and Greek colonial powers along the Black Sea coast became increasingly independent, Scythian control contracted to a core territory in Crimea and parts of the lower Dnieper. This power vacuum created opportunities for other groups, including proto-Slavic communities, to expand into previously Scythian-dominated territories.

Archaeological evidence indicates a gradual movement of agricultural settlements southward and eastward during this period. The distinctive pottery styles associated with proto-Slavic cultures began appearing in areas that had previously shown predominantly Scythian material culture. This expansion was not necessarily a coordinated process but rather a gradual movement of farming communities into territories that had become less controlled by Scythian political structures.

By the 1st-2nd centuries CE, as the last remnants of Scythian political power in Crimea succumbed to Sarmatian and Gothic pressures, Slavic expansion accelerated. The Zarubintsy and then Chernyakhov cultures, which incorporated substantial Slavic elements (though also Gothic and other influences), spread across much of what had been the northern Scythian sphere. This expansion continued into the early medieval period, with Slavic communities eventually forming the demographic foundation for the later Kyivan Rus' state that would emerge in the 9th century CE.

Archaeological Evidence of Interaction

Curled-up feline animal from Aržan-1, circa 800 BC (Photo: Zamunu45 CC BY-SA 4.0)

Burial Sites

Mortuary evidence provides some of the most detailed insights into Scythian-Slavic interactions. Traditional Scythian burials featured elaborate kurgan (burial mound) structures with rich grave goods, often including weapons, horse gear, and golden ornaments for elites. Proto-Slavic communities typically practiced cremation with more modest grave offerings. However, examination of burial sites in contact zones reveals interesting hybrid practices.

In the forest-steppe border regions, archaeologists have uncovered burial sites that display mixed characteristics. Some burials follow the physical structure of Slavic traditions but include Scythian-style grave goods, while others adopt aspects of Scythian burial construction but contain locally produced artifacts. Particularly revealing are certain cemetery sites in the middle Dnieper region where Scythian and proto-Slavic burials exist in close proximity, suggesting communities with mixed populations or at least close cultural contact.

Analysis of skeletal remains from these mixed burial zones has yielded evidence of violent trauma in some instances, confirming that armed conflict occurred between these groups. However, the prevalence of mixed cultural elements in many burials also suggests periods of peaceful coexistence and potential intermarriage between communities, particularly in later periods as rigid nomadic-sedentary distinctions began breaking down.

Settlement Patterns

The archaeological record of settlements provides further evidence of Scythian-Slavic interactions. Early proto-Slavic settlements typically featured small, unfortified farming communities with simple wooden structures. As contact with Scythian groups intensified, particularly in border regions, settlements began incorporating more substantial defensive elements including palisades, ditches, and earthen ramparts.

Excavations at sites in Ukraine and southern Russia have revealed settlements with mixed material cultures, containing both typically Scythian artifacts (such as characteristic arrowheads, horse fittings, and decorative metalwork) and proto-Slavic elements (particularly distinctive pottery styles and agricultural implements). The distribution of these items within settlements suggests that certain locations functioned as multicultural communities where both groups interacted regularly.

Particularly significant are fortified settlements like Bilsk in Ukraine's Poltava region, which covered an enormous area and showed evidence of both Scythian and proto-Slavic habitation. Such sites likely served as centers for trade, cultural exchange, and probably political negotiation between different groups, acting as buffer zones between the predominantly nomadic steppe regions and agricultural forest territories.

Historical Legacy

The centuries of interaction between Scythians and early Slavic peoples left a lasting imprint on the historical development of Eastern Europe. While the Scythians themselves eventually disappeared as a distinct cultural entity, elements of their material culture, military technology, and artistic traditions were incorporated into the developing cultures of the region, including those with significant Slavic components.

More broadly, the pattern of interaction established during this period—characterized by tension between nomadic steppe peoples and sedentary agricultural communities—would repeat throughout Eastern European history. Similar dynamics would play out in later centuries with the Sarmatians, Huns, Avars, Khazars, Pechenegs, Cumans, and finally the Mongols, all of whom would engage with Slavic populations along the forest-steppe frontier. The strategies developed by early Slavic communities for managing these relationships, including techniques of defense, diplomacy, trade, and cultural adaptation, provided templates that would be elaborated by their successors.

The eventual dominance of Slavic populations across this contested terrain represents not a simple military victory but rather the outcome of a complex historical process. Their agricultural lifestyle ultimately proved more demographically sustainable in the long term, allowing them to gradually expand into territories left vacant by the decline of nomadic powers or to absorb and assimilate nomadic groups that settled among them.

Conclusion

The relationship between Scythians and early Slavic peoples defies simple characterization as either primarily hostile or cooperative. Rather, their interactions spanned the full spectrum of human relationships, from violent conflict to peaceful trade, cultural exchange, and eventual integration. The archaeological and historical record reveals a complex frontier zone where different economic systems, military traditions, and cultural practices came into contact, creating patterns of both conflict and accommodation.

The study of Scythian-Slavic relations reminds us that ancient frontier zones were rarely simple boundaries between clearly defined groups but rather complex regions of interaction where identities were fluid and adaptable. While military confrontations certainly occurred, with Scythian cavalry raids representing a persistent threat to agricultural communities, evidence of trade and cultural borrowing demonstrates that even amid conflict, pragmatic cooperation and mutual influence continued.

As modern archaeological techniques reveal more details about this historical relationship, we gain a more nuanced understanding of how different societies with contrasting economic systems and cultural traditions negotiated their coexistence. The story of Scythian-Slavic relations thus provides not only insight into an important chapter of Eastern European history but also a case study in the complex dynamics of intercultural frontier zones throughout human history.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Were the Scythians and Slavs ethnically related peoples

No, the Scythians and Slavs belonged to different ethno-linguistic groups. The Scythians spoke an Iranian language belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch of Indo-European languages, while the Slavs spoke Proto-Slavic, belonging to the Balto-Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. Genetically and culturally, they developed as distinct populations, though some mixing occurred in contact zones.

2. Did the Scythians conquer and rule over Slavic territories?

While Scythian military campaigns certainly penetrated into territories inhabited by proto-Slavic peoples, there is limited evidence for long-term political domination or direct rule. Rather than formal conquest, their relationship appears to have featured periodic raids, tribute collection from some communities, and fluctuating frontier zones rather than stable imperial control.

3. What caused the ultimate decline of Scythian power in relation to Slavic peoples?

Multiple factors contributed to declining Scythian influence, including military pressure from Sarmatian tribes to their east, changing climate conditions affecting steppe pastoralism, internal political fragmentation, and the gradual expansion of agricultural populations (including but not limited to Slavs) into previously nomadic territories. This was less a direct military defeat by Slavic forces than a broader regional transformation.

4. What weapons and military tactics did Slavic peoples use against Scythian raiders?

Early Slavic defensive strategies emphasized fortified settlements with wooden palisades, earthen ramparts, and defensive ditches. Their warriors typically fought as infantry using spears, axes, shields, and simple bows. Over time, some Slavic groups adapted by developing their own cavalry forces and adopting elements of steppe military technology, though never matching the Scythians' nomadic mobility advantage.

5. Is there evidence of peaceful cooperation between Scythians and Slavs?

Yes, archaeological evidence indicates significant trade relations between these groups, with certain settlements functioning as multicultural trading centers. Artifacts showing mixed cultural influences suggest periods of peaceful coexistence and cultural exchange alongside the more documented conflicts. Particularly in later periods, as some Scythian groups became more sedentary, evidence of integration and cultural blending increases.

References

Alekseev, A. Y. (2007). The Scythians: Asian Nomadic Horsemen of the 1st Millennium BC. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences.

Anthony, D. W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Barfield, T. J. (1993). The Nomadic Alternative. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Curta, F. (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ivantchik, A. I. (2011). The Funeral of Scythian Kings: The Historical Reality and the Description of Herodotus. In L. Bonfante (Ed.), The Barbarians of Ancient Europe: Realities and Interactions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Melyukova, A. I. (1995). Scythians of Southeastern Europe. In J. Davis-Kimball, V. A. Bashilov, & L. T. Yablonsky (Eds.), Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age (pp. 27-58). Berkeley: Zinat Press.

Petrukhin, V. (2007). The Early History of Old Russian Art: The Ritual Knife from Gnëzdovo. Historical Research, 84(224), 2-12.

Piotrowski, B. (1979). The Slavs and their Neighbors in the First Millennium. Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences.

Rolle, R. (1989). The World of the Scythians. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sedov, V. V. (2013). Slavs in the Early Middle Ages. Moscow: Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences.

Terenozhkin, A. I. (1976). Cimmerians and Scythians. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

Trubachov, O. N. (2003). Ethnogenesis and Culture of the Ancient Slavs. Moscow: Nauka.