Nova Anglia: The Lost Anglo-Saxon Colony by the Black Sea

In the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of 1066, England underwent profound political and social transformation as William the Conqueror and his followers displaced the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy. While many Anglo-Saxon nobles reluctantly accepted Norman rule or died resisting it, a significant number chose a different path entirely - voluntary exile from their homeland. Among the most fascinating yet little-known outcomes of this exodus was the establishment of a settlement known as "Nova Anglia" (New England) near the Black Sea. This settlement represents a remarkable chapter in medieval history that connects Anglo-Saxons with other Germanic peoples including the Goths who had inhabited the region centuries earlier.

The Anglo-Saxon Exodus Following the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest of England marked one of the most decisive turning points in English history. After William's victory at the Battle of Hastings, many Anglo-Saxon nobles found themselves in an impossible position. Their lands were systematically confiscated and redistributed to Norman followers, their political power stripped away, and their cultural identity threatened. By the mid-1070s, many Anglo-Saxon nobles had lost all hope of successfully overthrowing Norman rule, particularly after the death of King Sweyn II of Denmark (c. 1074-1076), whom they had hoped would come to their aid.

According to the Chronicon Universale Anonymi Laudunensis, written by an English monk at Laon in the early 13th century, and the Játvarðar Saga (the Icelandic Saga of Edward the Confessor) from the 14th century, a group of these disenfranchised Anglo-Saxon nobles made the fateful decision to leave England forever in around 1075. Led by an individual named Siward (or Sigurðr in the Icelandic text), described as the "earl of Gloucester," they assembled a sizeable fleet of ships (350 according to the Játvarðar Saga, 235 according to the Chronicon) and set sail from England, heading for the Mediterranean.

The Journey to Constantinople

Illustration by C. R. Green

The Anglo-Saxon exiles' journey was long and eventful. According to the medieval accounts, they sailed past Pointe Saint-Mathieu, Galicia, through the Straits of Gibraltar to North Africa. They captured the city of Ceuta, killing its Muslim defenders and plundering its wealth. From there, they seized Majorca and Minorca before continuing to Sicily. While in the Mediterranean, they learned that Constantinople was being besieged by "heathens" (likely the Seljuk Turks).

Upon arriving at Constantinople around 1075, the Anglo-Saxon fleet fought victoriously on behalf of the Byzantine Emperor, who is named as Alexius I Comnenus in both the Játvarðar Saga and the Chronicon, though historical evidence suggests the emperor at that time was actually Michael VII (1071-1078). This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that Alexius I, who ruled from 1081 to 1118, later made extensive use of English warriors in his forces, which may have led to his name being erroneously associated with their initial arrival.

The Varangian Guard and Beyond

The Byzantine Emperor, grateful for the Anglo-Saxons' military assistance, offered to take them into service as part of his elite Varangian Guard – the emperor's personal bodyguard unit that had previously been composed primarily of Scandinavians. While many accepted this offer, the Játvarðar Saga relates that Siward and other leaders desired a realm of their own to rule.

According to these sources, the emperor informed them of a territory that had formerly been under Byzantine control but was now occupied by "heathens." He granted this land to the English exiles, provided they could reconquer it. The land was reportedly located "six days' and nights' sail east and north-east from Constantinople," which corresponds with the Crimean peninsula and the northeastern Black Sea coast.

The Establishment of "Nova Anglia"

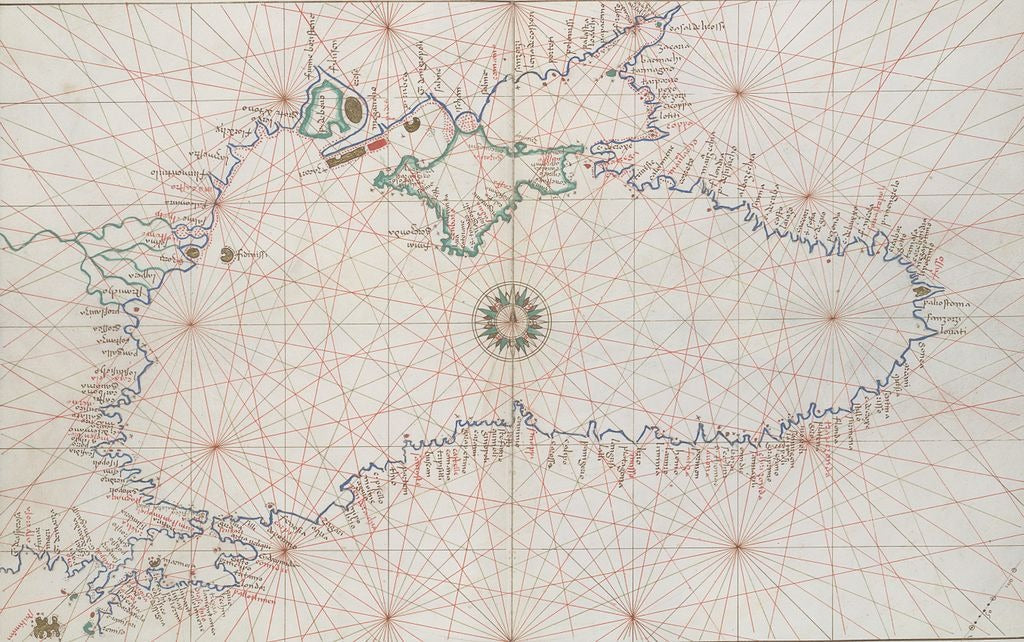

A 1553 nautical chart references flumen Londia and Porto di Susacho on the northeastern Black Sea coast, names possibly linked to London and Sussex, potentially supporting the existence of Nova Anglia.

The Anglo-Saxon exiles, led by Siward, successfully conquered this territory, driving away its previous inhabitants. They named their new colony "Nova Anglia" (New England), and according to the Játvarðar Saga, they named the towns after English cities:

"To the towns that were in the land and to those which they built they gave the names of the towns in England. They called them both London and York, and by the names of other great towns in England."

Remarkably, there is evidence beyond these two medieval texts that supports the existence of this colony. Portolan charts (medieval navigational maps) from the 14th to 16th centuries show place names in the region of the Crimean peninsula and northeastern Black Sea coast that appear to corroborate the Anglo-Saxon settlement. Names such as "Susaco" (possibly derived from "Saxon" or "Sussex"), "Londina" (clearly resembling "London"), and "Vagropoli" (City of the Varangians) appear on these maps.

Gothic Connections and the Historical Context

The region where Nova Anglia was established had a rich history of Germanic settlement that predated the Anglo-Saxon arrival by several centuries. The Goths, a Germanic people closely related linguistically and culturally to the Anglo-Saxons, had settled extensively around the Black Sea from the 3rd to 5th centuries CE.

The Ostrogoths and Visigoths had established significant kingdoms in the region before migrating westward under pressure from the Huns. By the time of the Norman Conquest, the Gothic kingdoms no longer existed as distinct political entities, but linguistic and possibly cultural elements remained. Scholars such as Ottar Grønvik have noted apparent West Germanic forms in the sparsely-recorded lexicon of Crimean Gothic dating from the 16th century, suggesting possible linguistic connections.

The Anglo-Saxon settlement in this region can be seen as a form of reconnection with their distant Germanic relatives' former territories. Both the Anglo-Saxons and the Goths shared common Germanic origins, despite centuries of separation and different historical trajectories. The Anglo-Saxons had converted to Christianity in the 6th-7th centuries, while the Goths had been Christianized even earlier, in the 4th century under Ulfilas, though initially as Arians rather than adherents of the Roman orthodoxy.

Evidence for New England's Continued Existence

The Nova Anglia colony appears to have survived for several centuries. In the mid-13th century, Franciscan friars on a mission to the Mongols reported encountering a people called the "Saxi" in the region, who were Christians living in well-fortified cities. These Saxi successfully resisted a siege by the Tartars through sophisticated military engineering and tactics, suggesting they maintained a formidable military capability.

According to the friars' account:

"When we were there we were told that the Tartars besieged a certain city of these Saxi and tried to subdue it. The inhabitants however made engines to match those of the Tartars, all of which they broke, and the Tartars were not able to get near the city to fight owing to these engines and missiles. At last they made an underground passage and bursting forth into the city they tried to set fire to it, while others fought, but the inhabitants posted a group to put out the fire, and the rest fought valiantly with those who had penetrated into the city and, killing many of them and wounding others, they forced them to retire to their own army. The Tartars, realising that they could do nothing against them and that many of their men were dying, withdrew from the city."

Further evidence comes from the mid-14th century De Officiis of Pseudo-Codinus, which stated that the Varangians at Constantinople still constituted a separate people and that, at Christmas, they wished the emperor length of life "in their native tongue, that is, English."

Religious and Cultural Identity

According to the Játvarðar Saga, the Anglo-Saxon settlers maintained their religious practices but with a significant twist:

"They would not have St. Paul's law, which passes current in Micklegarth [Constantinople], but sought bishops and other clergymen from Hungary."

This indicates that rather than adopting Eastern Orthodox Christianity (the dominant faith in the Byzantine Empire), they preferred to maintain connections with the Western Church. This choice reflects their desire to preserve their cultural identity and religious traditions even in exile.

The Legacy and Disappearance of Medieval New England

The fate of Nova Anglia remains unclear. It likely continued to supply fighters to the Varangian Guard at Constantinople, with reports of Englishmen in the Guard continuing into the early 15th century. Eventually, however, the settlement probably succumbed to the expanding power of the Mongols and later the establishment of the Crimean Khanate.

By the time of more extensive European exploration and mapping of the region in later centuries, the distinct Anglo-Saxon colony appears to have disappeared or been assimilated into the surrounding populations. The only remnants of their presence were the place names preserved on medieval maps and the historical accounts in the two medieval texts.

The story of the Anglo-Saxon "New England" by the Black Sea represents a fascinating chapter in medieval history that connects the displaced Anglo-Saxon nobility to both their Byzantine contemporaries and their distant Gothic relatives. While this colony has been largely forgotten in popular historical narratives, the evidence from medieval texts, place names, and contemporary accounts suggests it was a real and significant settlement that survived for several centuries.

The establishment of Nova Anglia demonstrates the remarkable mobility and adaptability of medieval peoples in the face of conquest and displacement. It also represents a unique instance of cross-cultural connection, as Anglo-Saxon exiles established themselves in a region once dominated by their Germanic cousins, the Goths, creating a new homeland far from the fields of England while maintaining elements of their cultural identity.

This medieval New England serves as a reminder that the full tapestry of history contains many threads that have faded from common knowledge but nonetheless played important roles in the complex interactions between peoples and cultures across the medieval world.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why did Anglo-Saxon nobles leave England after the Norman Conquest?

The Norman Conquest led to the systematic displacement of Anglo-Saxon nobles, with their lands confiscated and redistributed to Norman followers. After failed rebellions and the death of King Sweyn II of Denmark, whom they had hoped would help overthrow William the Conqueror, many nobles chose exile rather than living under Norman rule.

2. What evidence exists for the "New England" settlement by the Black Sea?

Evidence includes two medieval texts (the Chronicon Universale Anonymi Laudunensis and the Játvarðar Saga), place names on 14th-16th century portolan charts showing names like "Londina" and "Susaco" in the region, accounts from 13th-century Franciscan friars describing Christian "Saxi" in the area, and Byzantine records of English-speaking Varangians.

3. How did the Anglo-Saxons reach the Black Sea region?

According to medieval sources, they sailed from England through the Mediterranean, capturing Ceuta in North Africa and the Balearic Islands before reaching Constantinople. After helping the Byzantine Emperor defeat besieging enemies, some were granted territory to settle in exchange for reconquering it from "heathens."

4. What connection did these Anglo-Saxon settlers have with the Goths?

Both Anglo-Saxons and Goths were Germanic peoples with related languages and cultural backgrounds. The Goths had settled around the Black Sea in the 3rd-5th centuries CE, centuries before the Anglo-Saxon arrival. The Anglo-Saxon settlement in this region represented a kind of return to territory once inhabited by their distant Germanic relatives.

5. How long did the Nova Anglia colony survive?

While the exact duration is uncertain, evidence suggests it existed for at least 200 years. The settlement was established around 1075, and 13th-century accounts from Franciscan friars describe the "Saxi" still living in the region. References to English-speaking Varangians in Constantinople continue into the 14th century, with the last mentioned in 1404.

References

Chronicon Universale Anonymi Laudunensis (13th century)

Játvarðar Saga (Saga of Edward the Confessor, 14th century)

Green, C.R. (2015). "The medieval 'New England': a forgotten Anglo-Saxon colony on the north-eastern Black Sea coast." Retrieved from https://www.caitlingreen.org/2015/05/medieval-new-england-black-sea.html

Jacobs, F. (n.d.). "Another New England — in Crimea." Big Think. Retrieved from https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/another-new-england-nil-in-crimea/

Shepard, J. (1973). "The English and Byzantium: a study of their role in the Byzantine army in the later eleventh century." Traditio, 29, 53-92.

Shepard, J. (1978). "Another New England? — Anglo-Saxon settlement on the Black Sea." Byzantine Studies, 1, 18-39.

Fell, C. (1974). "The Icelandic saga of Edward the Confessor: its version of the Anglo-Saxon emigration to Byzantium." Anglo-Saxon England, 3, 179-196.

Dawson, C. (Ed. & Trans.) (1966). Mission to Asia: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New York.

Parker, E. (2019). Conquered: The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford University Press.