The Old Norse (Viking) Runes: Alphabet and Mysticism in the North

The Old Norse runes stand as both an alphabet and a complex cultural artifact of the Viking Age. Far beyond their role in basic communication, runes carried mystical and symbolic weight, employed in religious, legal, and magical contexts. Used primarily in Scandinavia between the 8th and 12th centuries, these characters represented more than phonetic values—they embodied power, fate, and cultural identity. Their origins stretch back to earlier Germanic traditions, but it is in the Viking Age that they became indelibly linked with Norse society.

The Origins of the Runes

The Svingerud Runestone, found near Oslo, Norway, is the world’s oldest datable runestone (1–250 CE). Its Elder Futhark inscriptions include the earliest known f‑u‑th sequence and a possible dedication reading “idiberug/idiberun.” (Photo: Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo)

The Elder Futhark

The earliest runic script is known as the Elder Futhark, named for its first six characters: ᚠ (F), ᚢ (U), ᚦ (Þ), ᚨ (A), ᚱ (R), and ᚲ (K). Consisting of 24 characters, the Elder Futhark was in use from roughly the 2nd to the 8th century CE. Archaeological evidence, including bracteates and tools, places its emergence in what is now Denmark and northern Germany. Scholars generally agree that the Elder Futhark was derived from a mix of Italic scripts, possibly North Etruscan, brought north through Germanic interactions with the Roman Empire.

Each rune of the Elder Futhark carried both a sound and a semantic meaning, often associated with natural forces, societal roles, or abstract concepts. This dual function—phonetic and symbolic—would remain central to the runic tradition.

The Transition to the Younger Futhark

By the late 8th century, the Elder Futhark was replaced by the Younger Futhark, a 16-character system used during the height of the Viking Age. This shift occurred during a period of significant linguistic change in the North Germanic languages. As the phonemic inventory of Old Norse evolved, so too did its writing system, albeit in ways that seem counterintuitive: fewer characters were now tasked with representing a greater number of sounds.

The Younger Futhark

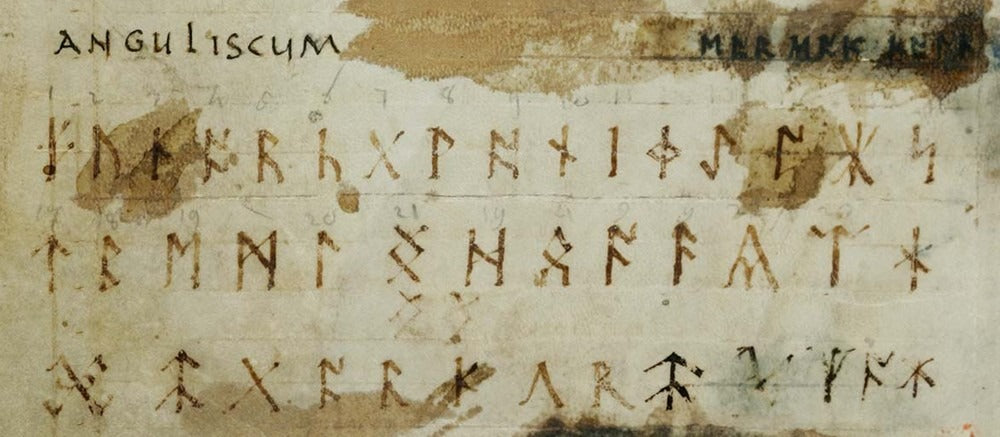

Long-branch and short-twig runes (Illustration by Tasnu Arakun)

Long-Branch and Short-Twig Variants

The Younger Futhark emerged in two primary forms: the long-branch (Danish) and short-twig (Swedish-Norwegian) variants. Both were used contemporaneously from the 9th to 12th centuries. The long-branch style was more decorative and formal, commonly found in runestones. The short-twig form, on the other hand, was typically used for everyday inscriptions and graffiti.

A third, rarer type—known as the staveless or Hälsinge runes—developed in central Sweden and is characterized by the absence of vertical staves. These regional variants suggest a living script adapted to specific cultural and material needs.

The Problem of Fewer Letters

One of the more curious features of the Younger Futhark is its reduction to 16 runes at a time when Old Norse phonology was becoming increasingly complex. This led to a situation in which one rune could represent multiple sounds. For example, the rune ᚦ (Þ) could denote both the voiceless [θ] and voiced [ð] “th” sounds. To disambiguate, context and rune placement were crucial. Inscriptions sometimes incorporated diacritical dots or additional runes to clarify meaning, but this was inconsistent.

Individual Runes of the Younger Futhark

Illustration of the runes by Spratmackrel (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Overview of the 16 Runes

The Younger Futhark comprises 16 core runes, each with an associated name, phonetic value, and cultural significance. The names are preserved in runic poems composed in Old Norse, Old English, and Old Icelandic, each shedding light on the symbolic meaning attributed to each rune.

Fé (ᚠ) to Yr (ᛦ): Names, Sounds, Meanings

Fé (ᚠ) means "wealth" or "cattle", anchoring the rune to material prosperity. Úr (ᚢ), meaning "drizzle" or "slag", evokes natural processes. Þurs (ᚦ) signifies a "giant", a clear link to Norse myth. Óss (ᚬ) translates to "god" or "mouth", reflecting divine or poetic speech. Reid (ᚱ) means "ride", linked to travel or journeys.

Kaun (ᚴ), denoting an "ulcer" or "boil", is associated with affliction. Hagall (ᚼ), or "hail", represents disruption. Nauðr (ᚾ), meaning "need", connotes hardship or compulsion. Ís (ᛁ) stands for "ice", a symbol of stillness and danger. Ár (ᛅ) means "year" or "good season", suggesting abundance.

Sól (ᛋ), the "sun", embodies clarity and strength. Týr (ᛏ), named for the god of law and war, represents justice. Bjarkan (ᛒ), a "birch tree", implies growth. Madr (ᛘ) means "man", symbolizing human existence. Lögr (ᛚ), or "water", evokes fluidity. Yr (ᛦ) is associated with "yew" or the bow, often linked to endings or death.

Runes as Tools of Writing and Power

The Vimose Comb, found on the island of Funen in Denmark, bears one of the earliest known runic inscription, dating to around 150–200 AD. It reads ᚺᚨᚱᛃᚨ (“Harja”), a male name. (Photo: Nationalmuseet CC BY-SA 3.0)

Inscriptions and Communication

Runes were carved into stone, bone, metal, and wood. The vast number of runestones found in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway—many commemorative in nature—demonstrates that runes were widely used for memorializing the dead, asserting claims to land, or proclaiming victories. In some cases, inscriptions were purely informative, such as marking ownership or denoting a maker.

Some inscriptions were composed in verse, suggesting that rune carving was not a rote task but a literary act. The craftsmanship involved and the permanence of stone indicate that public rune carving carried significant weight.

Magical and Ritual Uses

Elder Futhark runic inscription on one of the replicas of the Golden Horns of Gallehus found in Jutland, dating back to the 5th century (Photo: Bloodofox CC BY-SA 3.0)

Runic Charms and Galdr

Runes also functioned in the realm of the supernatural. The use of runes in charms, incantations (galdr), and talismans is well-documented in sources like the Poetic Edda and sagas such as Egils saga Skallagrímssonar. In this text, the protagonist inscribes healing runes on a drinking horn to save a dying woman. These practices suggest a belief in the inherent power of the runes themselves.

Legal and Protective Inscriptions

Some runic inscriptions served legal or protective functions. In Norway, a runic stick from Bergen contains a legal curse threatening anyone who breaks an agreement. Protective inscriptions invoking deities or abstract forces were common, especially on weapons or personal items. The Ribe skull fragment (c. 800s CE) contains runes believed to ward off harm or malevolent spirits.

Christianization and Decline

The Saleby Church bell (from Västergötland), inscribed with runes and Christian crosses from 1228 AD (Photo: Erik Brate)

Runic Use into the Middle Ages

Even after Christianization, runes did not disappear immediately. In fact, runic inscriptions in Scandinavia increased during the 11th century. However, the content gradually shifted: Christian crosses and prayers began to appear alongside traditional rune forms, reflecting a transitional religious landscape.

Latin script eventually became dominant, particularly as it was tied to the Church and administrative power. Still, runes continued in rural areas, especially in Sweden, into the 14th century. The so-called "medieval runes" (used 1100–1500 CE) adapted the Latin alphabet to runic forms.

Suppression and Survival

Though not formally outlawed, runes came to be associated with paganism and superstition. Their use in magic or folk medicine drew suspicion, especially during the Reformation and later witchcraft panics. However, interest in runes persisted in antiquarian circles, especially during the 17th-century Scandinavian Renaissance and later Romantic movements.

The Old Norse runes were far more than a writing system. They served as a medium through which the Vikings recorded their deeds, expressed their beliefs, and navigated both the seen and unseen dimensions of life. Each rune bridged the realms of sound and symbol, law and lore, speech and sorcery. Though ultimately supplanted by the Latin alphabet during the Christianization of Scandinavia, the runes have never truly vanished.

Even today, the runic alphabets—Old Norse, Anglo-Saxon, and others—remain accessible to modern learners. In some ways, their structure aligns more naturally with the phonology of their original languages than the Latin script ever did. For Old Norse, Old English, and related tongues, runes often offer a more intuitive match, capturing sounds and meanings that Roman letters tend to obscure. Beyond academic study, runes persist as cultural emblems, artistic motifs, and symbols of ancestral identity. Their continued relevance in everything from historical reconstruction to modern neopagan traditions testifies to their enduring power. The runes remain not just relics of the Viking past, but living links to the linguistic and spiritual heritage of the North.

ᚸ

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why did the Younger Futhark have fewer characters than the Elder Futhark?

It reflected linguistic shifts in Old Norse, but the reason for reducing to 16 characters despite increased phonemic diversity remains debated among scholars.

Were runes used for everyday writing?

Yes. Runes were used in graffiti, trade, and legal documents, especially on wooden sticks and bone in urban centers like Bergen.

Did Vikings believe runes had magical power?

Yes. Literary sources and archaeological finds suggest runes were believed to hold magical or protective properties when used in charms or rituals.

How long were runes used after Christianization?

Runes remained in use into the 14th century, especially in rural Sweden, although Latin script became dominant from the 12th century onward.

Are any runes still used today?

While not used in formal writing, runes are studied academically and used symbolically in modern cultural, spiritual, and artistic contexts.

References

Page, R. I. Runes: Reading the Past. British Museum Press, 1987.

Barnes, Michael. Runes: A Handbook. Boydell Press, 2012.

Spurkland, Terje. Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions. Boydell Press, 2005.

Williams, Henrik. “Runes.” In The Viking World, edited by Stefan Brink and Neil Price. Routledge, 2008.

MacLeod, Mindy, and Mees, Bernard. Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. Boydell Press, 2006.