The Æsir and the Anses: Tracing Divine Ancestry in Germanic Tradition

In the pre-Christian belief systems of the Germanic peoples, the divine and the ancestral were not always distinct categories. The gods of these societies did not emerge fully formed from abstract mythology but often bore the attributes of long-revered chieftains, kings, or culture-heroes. Germanic tribes from Scandinavia to the North Sea coast venerated a pantheon known as the Æsir, a term rooted in older linguistic traditions that may once have simply meant "god" or even "ancestor." The notion that the gods were once mortal men, elevated by memory and ritual, permeates the traditions and literary fragments of the Germanic world.

This article approaches the topic specifically from the perspective of the gods as deified ancestors and is not intended to discredit or diminish the beliefs of those who regard these figures as literal deities. The goal is to explore one cultural and historical lens among many that shaped early Germanic religious traditions.

This belief system was more than theological—it was sociopolitical. Ancestral deification solidified claims to territory, heritage, and tribal unity. Jordanes, the 6th-century Roman-Gothic historian, provides a rare insider account that explicitly identifies divine figures as former kings. Although modern academia sometimes critiques Jordanes for possible bias due to his Gothic heritage, this article takes the position that his lived experience as a Goth lends his testimony greater reliability. He was not merely reporting from the outside; he lived among the people he wrote about before becoming part of the Roman world. When placed alongside linguistic evidence and naming customs across Germanic tribes, a pattern emerges: a religion built on reverence for the dead, elevated through narrative and worship.

The Word "Æs" and Its Connection to the Æsir

Snæfell in Iceland, where Barðr Snæfellsáss, according to Barðar saga, became a local guardian spirit (áss) revered by the people for his protection over the region. (Photo: Axel Kristinsson CC BY 2.0) Ask ChatGPT

Origins of the Term Æs and Proto-Germanic Roots

The Old Norse term “Æsir” (singular "Áss") is commonly used to describe the principal gods of the Norse pantheon, such as Odin, Thor, and Tyr. Linguistically, this word stems from the Proto-Germanic *ansuz, which likely carried a general meaning of "deity" or "spirit-being." Yet earlier uses may have included meanings such as "ancestor" or "divine forefather," particularly in poetic and religious contexts. The same root appears in Old English as "ēse" or "ēas," and in Gothic as "ansis," a term used by Jordanes to describe ancient Gothic kings who were elevated to divine status.

The Æsir as Divine Ancestors in Norse Mythology

Many of the Æsir possess traits that reflect archetypal rulers, warriors, and lawgivers, rather than abstract gods of nature or metaphysics. Odin, often portrayed as the all-father, exhibits qualities of a historical war-leader and chieftain. His association with knowledge, poetry, and kingship mirrors the functions of a tribal patriarch. These characteristics suggest a transformation from ancestral hero to god, reinforced through oral tradition and ceremonial rites.

In some lesser-known folk tales, Odin is remembered not simply as a deity, but as a migrating chieftain who led his people from a distant homeland. One version—promoted, though not necessarily invented, by Snorri Sturluson—claims that Odin came from Troy, gathering his followers and settling them in northern lands. Though this account is often viewed through a mythological lens, it may reflect an ancestral memory of displacement or forced migration from someplace. Rather than a peaceful journey, the narrative implies a departure driven by crisis, echoing broader Indo-European patterns where people preserved the trauma of lost homelands in the form of legendary wanderings. Similar motifs appear in the Irish claim of Scythian descent, which—though not historically precise—aligns with genuine patterns of prehistoric movement from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. For Odin, this legacy of exile and leadership imbues his “Allfather” role with greater depth: not only as a spiritual progenitor, but as a protector and guide who bore the weight of his people’s survival.

Jordanes and the Gothic Perspective

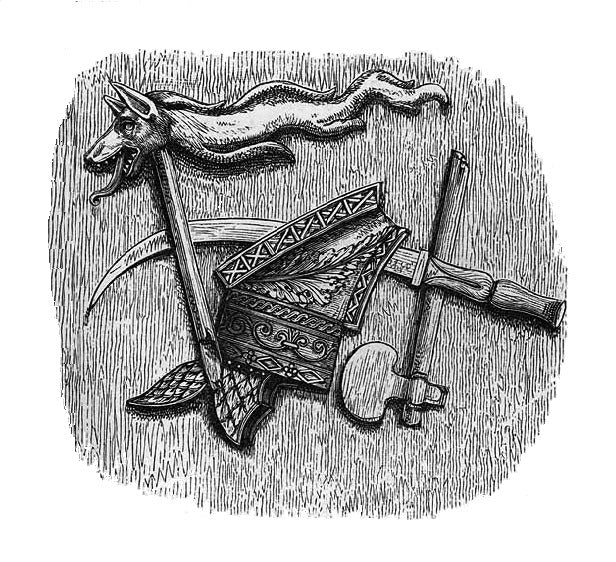

Getica: The Origin and Deeds of the Goths by Jordanes

The Getica and the Divine Lineage of the Goths

Jordanes, writing his Getica around 551 AD, recounts the lineage of the Gothic people and their early migration - that being before the official Migration Period, as early as 500 BC. He explicitly refers to the earliest Gothic kings as "Anses," a term he equates with demigods or deified ancestors, and is linguistically in cognate with Æsir and Áss. According to his narrative, these figures were remembered not as abstract mythological constructs but as noble forebears whose legacy commanded religious reverence. Their deeds, etched into tribal memory, elevated them to divine status, reflecting a form of hero cult that bridged history and myth.

"They took up arms and presently overwhelmed the Romans in the first encounter. They slew Fuscus, the commander, and plundered the soldiers' camp of its treasure. And because of the great victory they had won in this region, they thereafter called their leaders, by whose good fortune they seemed to have conquered, not mere men, but demigods, that is Ansis." - Jordanes, The Getica XIII

Roman-Gothic Cultural Interplay

Though Jordanes was writing within the framework of Byzantine Latin historiography, his account preserves Gothic oral traditions. His portrayal aligns with similar Roman practices of apotheosis, in which emperors were declared divine upon death. The Gothic Anses thus appear to be a local manifestation of a broader Indo-European tradition of ancestor deification, adapted to a Germanic context.

Eponymous Progenitors of Germanic Tribes

Depiction of the two brothers Dan and Angul by Gudmund Hentze

Angul, Dan, Saxnot, and Other Founding Figures

Nearly all early Germanic tribes trace their identity to a legendary founder, often considered semi-divine. The Angles are said to descend from Angul; the Danes from Dan; the Saxons from Saxnot (Seaxnēat), who was also worshipped as a god; and the Franks from Francio. These figures appear in royal genealogies, often placed at the intersection of myth and remembered history. Their inclusion in sacred or epic narratives suggests a status well beyond mortal, at least within the worldview of their descendants.

This tradition was not limited to tribal founders. It extended into the genealogies of heroic families whose lineages were preserved in later legendary material. The Volsungs, for example, claimed descent from Odin and featured prominently in Norse heroic sagas, with figures like Sigmund and Sigurðr portrayed as more than mortal. Likewise, the Ynglings—early rulers of Sweden and Norway—were said to descend directly from the god Freyr, blending royal legitimacy with divine heritage. Similar themes appear in the Skjöldung lineage of Denmark, descended from Skjöldr, another son of Odin. These ancestral myths functioned as more than oral tradition—they reinforced social structure, justified leadership, and maintained cultural memory through the sanctification of ancestry.

Tribal Naming Practices and Hero Cults

Such tribal eponyms were not only symbolic but functioned as legitimizing devices for ruling houses. By aligning themselves with divine ancestors, tribal leaders gained sacral authority. Hero cults may have formed around burial sites, battlefields, or other places associated with these figures. The practice reflects a deep intertwining of genealogy, myth, and religious practice in Germanic society.

Shared Features with Other Indo-European Ancestor Veneration

Pendant showing Alexander the Great as Zeus Ammon, complete with ram’s horns and a diadem. Worn as an amulet in the 4th-century Roman world, it blended divinity and kingship.

Parallels with Roman and Indo-Iranian Traditions

Ancestor worship was not unique to the Germanic world. Roman religion included the cult of the divi, or deified emperors, and the lares and manes, household spirits representing deceased ancestors. In Indo-Iranian contexts, ancestral spirits were similarly honored through fire rituals and hymns. The Germanic practice, though distinct in symbolism and cosmology, fits within this wider Indo-European phenomenon.

Differences in Function and Representation

What distinguishes Germanic traditions is the degree to which these ancestral figures were absorbed into an active, martial pantheon. Rather than being relegated to household cults or seasonal rites, the Germanic gods derived from ancestors became central actors in mythic cosmology, influencing war, fate, and kingship. This shift reflects both the militarized nature of early Germanic societies and the enduring power of lineage.

Linguistic and Cultural Traces of Deified Ancestors

The greatest extent of Dacian influence, this map highlights various tribes of Scythia, including the Getae, the Tyragetae—whose name combines the Gothic ‘Getae’ with the god Tyr—and the Buri, possibly linked in name to Búri, the progenitor of the Norse gods. (Illustration: Portasa Cristian CC0)

Odin and Godan: A Linguistic Bridge?

The god Odin, also known as Wodan or Wotan in various Germanic tongues, appears in Lombard tradition under the name "Godan" or "Goden." This variation reflects phonological patterns in West Germanic languages, where "d" and "th" sounds often overlap or interchange. While some scholars interpret these shifts as merely dialectal, others consider them linguistic clues pointing to a shared mythic ancestor or at least a common cultural framework. The proximity of the name "Goden" to "Goth" or "Got" has led to speculation about a deeper connection between the Goths and the figure of Odin.

Though this remains a theory rather than a proven fact, it is notable that multiple historical sources, including Jordanes, describe the Goths as descendants of gods or demi-gods. The Gothic royal line, particularly the Amal dynasty, is referred to in ancient songs as the "Anses"—a term strongly associated with divine ancestry. If "Goth" and "Godan" do share etymological roots, the implications would reinforce a self-conception among the Goths as not merely a people with divine ancestors, but as heirs to a sacred bloodline—possibly even tied to the highest of the Æsir himself. While definitive linguistic proof remains elusive, the alignment of names, traditions, and ancestral claims makes the possibility a compelling one.

Speculative Connections with Freyr, Freyja, and Frisian Identity

While no direct evidence links the Frisian people to the deities Freyr or Freyja, the similarity in names has inspired some speculative theories. Given the cultural importance of fertility, land, and kinship in both Frisian and Old Norse societies, some argue for a common cultic origin. However, such connections remain conjectural and lack firm linguistic or archaeological corroboration.

Conclusion

The tradition of deifying ancestors among the Germanic peoples reflects a deeply rooted worldview in which lineage and divinity were intertwined. From the Anses of the Goths to the legendary founders of Germanic tribes, the sacred was embedded in memory, narrative, and bloodline. This belief system allowed mortals to ascend to godhood through communal reverence, shaping the religious and political structures of early Europe. While some details remain speculative or fragmentary, the overall pattern is unmistakable: the gods of the Germanic world were once men.

But their elevation was never just about immortalizing a single individual. These figures stood as symbols of a living kin-chain, sources of pride and aspiration whose names shaped the identity of entire tribes. Their stories offered more than comfort—they offered direction. Just as Caesar reportedly found his calling in the shadow of Alexander, so too did young warriors and leaders among the Germanic peoples look to Angul, Saxnot, Dan, and others not as distant myths, but as blood-bound exemplars. In this tradition, to honour one's ancestor was not passive remembrance but active participation in an ongoing legacy. The past was not a place left behind—it was a fire to be carried forward. Through this, the Germanic ethos bound generations together, forging a culture where greatness was never claimed in isolation, but inherited, extended, and handed on.

ᚸ

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does "Æsir" mean in Germanic mythology?

The Æsir are the principal gods of Norse mythology. The term is derived from Proto-Germanic *ansuz and may have originally referred to deified ancestors.

Who was Jordanes, and what did he say about Gothic ancestors?

Jordanes was a 6th-century Roman bureaucrat of Gothic descent. In his work Getica, he described the Gothic founders as "Anses," meaning deified kings or demigods.

Did all Germanic tribes claim descent from gods?

Most early Germanic tribes traced their lineage to a legendary ancestor who was often deified, such as Angul, Dan, or Saxnot.

Is there a connection between Odin and historical figures?

Some scholars believe Odin may be a mythologized composite of real chieftains. The Lombard form "Godan" supports the idea of a shared ancestral origin.

Are Freyr and Freyja linked to the Frisians?

There is no direct evidence of this, though the similarity in names has led to speculative connections. Such theories remain unproven.

References

Jordanes, Getica. Trans. Charles Mierow, 1915.

de Vries, Jan. Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1957.

Simek, Rudolf. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Trans. Angela Hall. Boydell, 2007.

Lindow, John. Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Davidson, H.R. Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books, 1964.

Bek-Pedersen, Karen. The Norns in Old Norse Mythology. Dunedin Academic Press, 2011.