Serpents in Norse and Germanic Mythology: Sacred Symbols and Fearsome Beasts

The serpent held a position of profound importance in Norse and Germanic cultures, serving as both a symbol of cosmic order and chaos. Archaeological evidence dating from the Migration Period (400-550 CE) through the Viking Age (793-1066 CE) demonstrates the perpetual presence of serpentine imagery in Northern European artistic and religious expression.

Pre-Viking Age Serpent Symbolism

During the Migration Period, serpent motifs appeared frequently on bracteates and ceremonial objects. These early representations often showed intertwined serpents, suggesting a connection to fertility and regeneration. The 6th-century Alemanni belt buckles found in modern-day Germany frequently featured serpentine designs, indicating the widespread nature of this symbolism.

Archaeological Evidence

Excavations across Scandinavia have yielded numerous artifacts bearing serpent imagery. The Oseberg ship burial (834 CE) contained several wooden carvings with intricate snake motifs, while the Jelling stones (965 CE) in Denmark showcase prominent serpentine designs interweaved with other mythological elements.

Major Serpent Figures in Norse Mythology

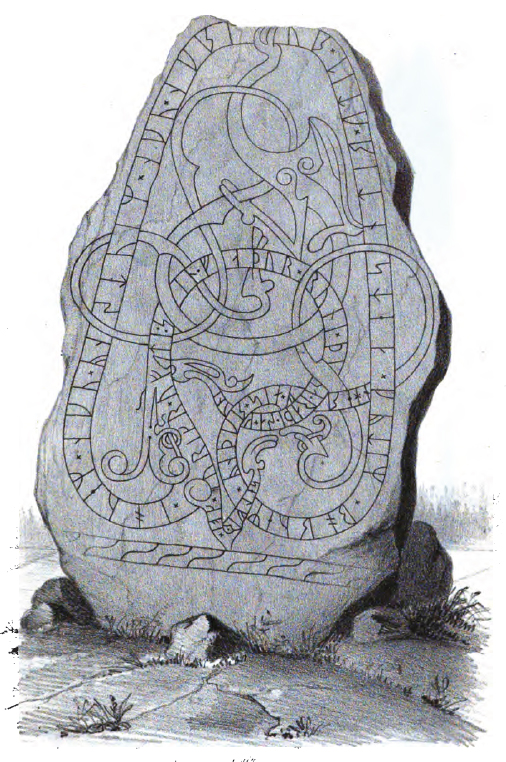

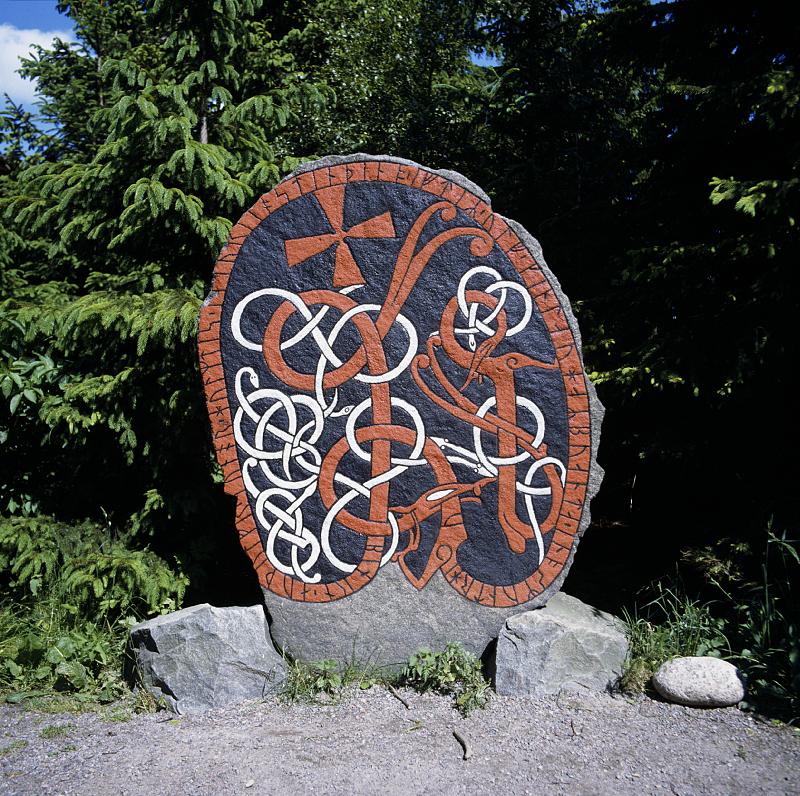

Runestone U 887 from Skillsta, Sweden, featuring a depiction of a dragon with wings and two legs intricately carved in stone.

Jörmungandr: The World Serpent

Jörmungandr, the Midgard Serpent, stands as perhaps the most significant serpent figure in Norse mythology. According to the Prose Edda, this offspring of Loki grew so large that it encircled Midgard (the world of humans), grasping its own tail. The serpent's presence maintained cosmic balance, though its eventual release would herald Ragnarök.

Níðhöggr and Yggdrasil

At the base of Yggdrasil, the world tree, dwelled Níðhöggr, a malevolent serpent that gnawed at the tree's roots. The creature's presence in the mythology represents a constant threat to cosmic order, as its actions could potentially destabilize the world tree that connected the Nine Worlds.

Serpent Symbolism in Germanic Art

Norse Germanic Serpent Motif Elder Futhark Rune Ring

Runestones and Memorial Stones

Serpentine imagery features prominently on runestones throughout Scandinavia. The Jellinge style (10th century CE) particularly emphasized serpentine interlace patterns. These designs often framed runic inscriptions, serving both decorative and possibly protective functions.

Metalwork and Jewelry

Viking Age metalwork frequently incorporated serpent motifs. The Urnes style (late 11th century) showed particular sophistication in its serpentine designs, with elegant, sinuous creatures adorning everything from broaches to sword hilts.

Literary References and Sagas

Depiction of Nidhogg (Illustration: Paganheim).

Poetic Edda References

The Poetic Edda, compiled around 1270 CE but containing much older material, offers numerous references to serpents. In "Grímnismál," four serpents - Góinn, Móinn, Grábakr, and Grafvölluðr - are described slithering beneath Yggdrasil. The poem "Völuspá" specifically mentions Níðhöggr carrying corpses in its wings, suggesting a complex hybrid creature rather than a simple serpent.

Saga Narratives

The Völsunga saga, dating from the 13th century, contains the notable account of Gunnar being thrown into a snake pit. This narrative demonstrates how serpents were often associated with both death and testing of heroic valor. The saga also includes the famous episode of Sigurd cooking Fafnir's heart, where understanding the speech of birds comes from tasting dragon's blood.

Modern Archaeological Findings

Lindworm carving on the U 871 runestone. (Photo: Bengt A. Lundberg, CC BY 2.5)

Recent archaeological discoveries have continued to enhance our understanding of serpent symbolism in Norse culture. The 2017 excavations at Gamla Uppsala revealed several previously unknown snake motifs on burial goods, while underwater archaeology in Danish waters has uncovered ship parts bearing serpentine decorations dating to the 9th century.

The Oseberg ship burial, excavated in 1904-1905 but still yielding new insights through modern analysis techniques, contains numerous items decorated with snake motifs. Recent X-ray fluorescence studies of these artifacts have revealed previously invisible design elements, suggesting even more extensive use of serpentine imagery than initially thought.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

One of four carved dragon heads that adorn the ridges of the Borgund Stave Church in Norway. (Photo: Bjørn Erik Pedersen, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The influence of Norse serpent symbolism extends well beyond the medieval period. Modern Scandinavian art and design frequently incorporate these ancient motifs, while contemporary pagan movements often reference the cosmic symbolism of Jörmungandr and other mythological serpents.

The archaeological record demonstrates a clear evolution of serpent imagery from the Migration Period through the Viking Age and into the Medieval period. This evolution reflects changing religious beliefs and artistic traditions, while maintaining core symbolic elements that remained meaningful to Norse and Germanic peoples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What was the significance of Jörmungandr in Norse mythology?

Jörmungandr, the World Serpent, was believed to encircle Midgard (Earth), maintaining cosmic balance. During Ragnarök, it would release its tail and battle Thor, resulting in their mutual destruction.

- How were serpents depicted in Viking art?

Vikings depicted serpents in various artistic styles, including the Jellinge, Mammen, and Urnes styles. They were often shown intertwined, forming complex patterns, and sometimes incorporated into larger decorative schemes with other animals.

- What role did Níðhöggr play in Norse cosmology?

Níðhöggr was a serpent that gnawed at the roots of Yggdrasil, the world tree. It represented a constant threat to cosmic order and was associated with death and decay.

- Were serpents viewed positively or negatively in Norse culture?

Serpents held an ambiguous position in Norse culture, representing both protective and destructive forces. They were associated with wisdom and power but also with chaos and destruction.

- What evidence exists for serpent worship in Germanic cultures?

Archaeological evidence includes decorated bracteates, runestones, and ritual objects bearing snake motifs. Literary sources also mention serpents in religious contexts, though direct evidence of worship is limited.

References and Sources

Andrén, Anders. (2014). "Tracing Old Norse Cosmology: The World Tree, Middle Earth, and the Sun from Archaeological Perspectives." Nordic Academic Press.

Price, Neil. (2020). "Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings." Basic Books.

Pluskowski, Aleksander. (2010). "Medieval Animals and Their Meanings." Cambridge University Press.

Gräslund, Anne-Sofie. (2019). "The Twilight of the Gods: Archaeological Evidence for Norse Religion." Uppsala University Press.

Hedeager, Lotte. (2011). "Iron Age Myth and Materiality: An Archaeology of Scandinavia AD 400-1000." Routledge.

Lindow, John. (2002). "Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs." Oxford University Press.

Müller-Wille, Michael. (2007). "Scandinavian Art during the Viking Age." Medieval Archaeology Journal, 51, 229-250.

Davidson, H.R. Ellis. (1964). "Gods and Myths of Northern Europe." Penguin Books.

"Runestone (Sö 173)" by Daniel Langhammer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.