Uncovering a Viking Ship Part Beneath Oslo’s Modern Streets

The discovery of a ship part from the late 11th century beneath the modern streets of Oslo provides a rare glimpse into the transitional period between the Viking Age and the medieval era. Found during an archaeological excavation in Bjørvika, a historic harbor at the innermost part of the Oslofjord, this artifact reveals both advanced shipbuilding techniques and the enduring influence of Viking seafaring traditions.

Bjørvika: A Maritime Time Capsule

Modern day Bjørvika, with its Oslo's Opera House at the centre (Photo: DangerMouse CC BY-SA 4.0)

For centuries, the seabed in Bjørvika has been a repository of Norway’s maritime history. Located just a few hundred meters from Oslo’s bustling Opera House and Barcode district, the area has yielded numerous shipwrecks, primarily dating from the 14th to 17th centuries. These finds paint a vivid picture of Oslo’s evolution as a trading hub.

Archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) were prepared to encounter medieval artifacts during their investigation, but the discovery of an exquisitely crafted ship part presented a unique challenge to their expectations.

“This piece of wood was fantastically well-formed,” archaeologist Håvard Hegdal noted, emphasizing its aesthetic and technical sophistication.

A Piece of History Dated to the Late 11th Century

Initially assumed to be contemporary with the nearby 14th-century wharf, the ship part underwent dendrochronological analysis, a precise dating method based on tree ring patterns. The results were startling: the wood originated from an oak that sprouted in 1035 and was felled between 1087 and 1100.

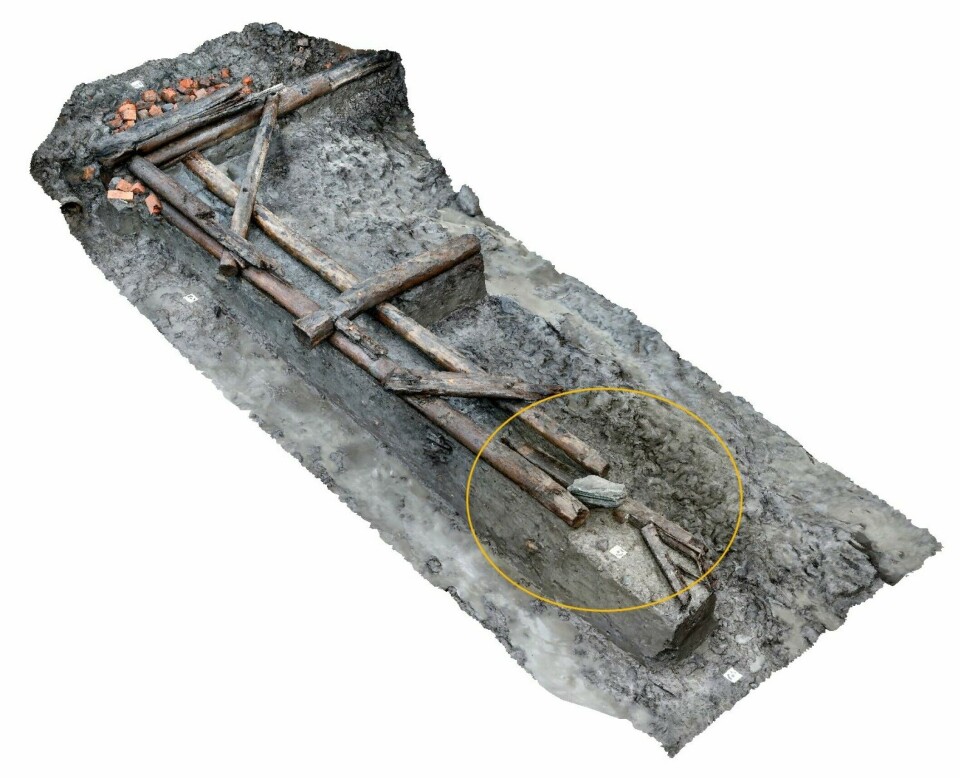

Beneath the foundation of a 14th-century wharf, archaeologists uncovered a ship part, marked in the photo just below the stone to the right. (Photogrammetry: Cornelia Eilertsen / NIKU)

The artifact’s age situates it at the very end of the Viking Age, a time marked by the waning dominance of Viking maritime culture and the rise of medieval trade networks.

Shipbuilding at the Crossroads of Eras

The Bjørvika ship part, a central component where the mast was mounted, stands out for its meticulous craftsmanship. Unlike the utilitarian design of many medieval cargo vessels, this piece featured decoration on all sides, including areas not visible during use. Such detailing suggests a combination of functional innovation and aesthetic tradition, reflecting the enduring Viking emphasis on maritime artistry.

This ship part features intricately inlaid wooden plugs. (Screenshot made by sciencenorway.no from NIKU video)

Hegdal remarked on its uniqueness:

“There’s an aesthetic quality to the ship part we’ve found that we don’t find in the more roughly hewn parts from cargo ships and work ships made in the Middle Ages.”

Although less elaborate than earlier Viking ships like the Gokstad, the Bjørvika artifact demonstrates a continuity of sophisticated maritime technology.

The Mystery Beneath the Wharf

The location of the ship part, buried beneath a wharf dated to around 1300, raises intriguing questions. How did a 200-year-old artifact come to rest beneath later medieval infrastructure?

One possibility is that the part was salvaged and repurposed before being abandoned. Alternatively, it may have been preserved as a relic of a bygone era, later incorporated into the harbor’s evolving landscape.

The exceptional preservation conditions in Bjørvika’s clay-rich seabed have ensured that such artifacts remain remarkably intact, offering unparalleled insights into Norway’s maritime heritage.

Broader Implications for Viking Age Studies

The Bjørvika find underscores the transitional nature of the late 11th century, a period when the Viking Age’s seafaring traditions began to merge with emerging medieval practices.

Harald Hardrada, the Last Great Viking King (Photo: Paganheim.com)

Oslo, founded by Harald Hardrada in 1048, was a burgeoning trading center during this time. The ship part’s craftsmanship and location hint at the city’s role as a nexus of cultural and technological exchange.

Moreover, this discovery contributes to a growing understanding of how Viking maritime innovations influenced subsequent generations, bridging the gap between raiders and merchants.

Visualizing the Past

To better interpret this find, diagrams comparing the Bjørvika artifact’s design with Viking Age and medieval shipbuilding techniques would be invaluable. Additionally, a visual timeline of Oslo’s development as a maritime hub could contextualize the artifact within the broader historical narrative.

Conclusion

The Bjørvika ship part serves as a tangible link to a pivotal era in Norway’s history. Its discovery not only enriches our understanding of late Viking Age craftsmanship but also highlights the dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation in a rapidly changing world.

As archaeologists continue to uncover Bjørvika’s secrets, this artifact reminds us of the enduring legacy of Norway’s seafaring ancestors and the stories embedded in their ships.

References

Amundsen, B. (2024). This ship part found in Norway is much older than archaeologists first thought. Science Norway.

Hegdal, H., & Eilertsen, C. (2024). Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research.

Various Authors. (2024). Dendrochronology and its applications in archaeological dating. NIKU Reports.