Article: Anglo-Saxon Art and Jewelry: Brooches in Cultural and Germanic Context

Anglo-Saxon Art and Jewelry: Brooches in Cultural and Germanic Context

Throughout the early medieval period in England, jewelry—especially brooches—played a vital role in the expression of identity, status, belief, and heritage. From the fifth to the eleventh centuries, Anglo-Saxon artisans developed distinctive brooch forms that reflected both local tastes and broader Germanic traditions. While Anglo-Saxon art encompassed a range of media, brooches provide the most abundant and informative material record. Found in graves, hoards, and settlements across the country, they offer one of the clearest and most tangible insights into the visual culture of the period. Their forms, materials, and motifs reveal both continuity with earlier migration-era Germanic styles, such as Gothic fibulae, and the unique evolution of aesthetic traditions within Anglo-Saxon England.

Early Anglo-Saxon Brooch Types (5th–6th centuries)

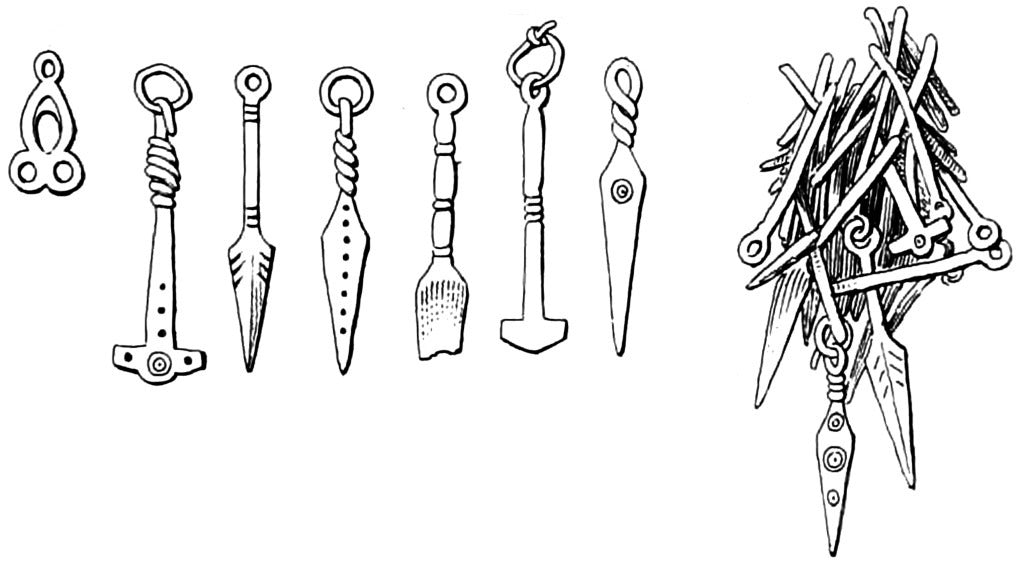

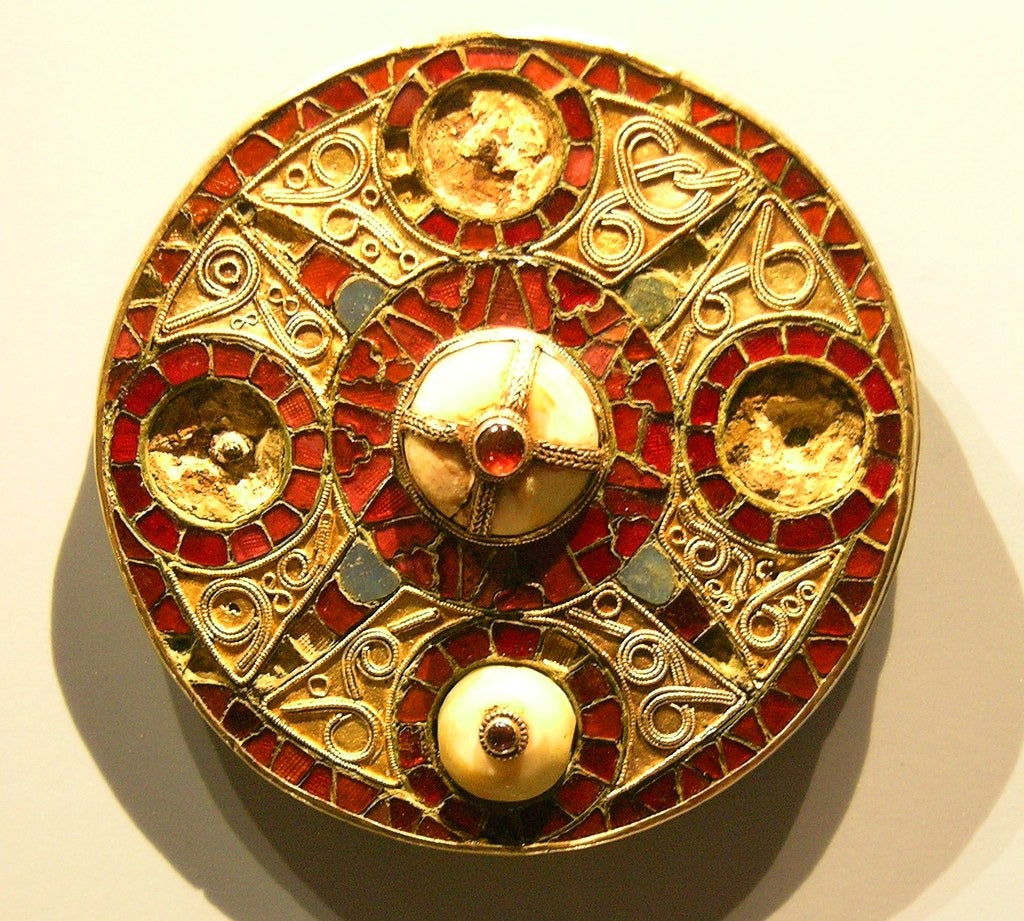

Grave assemblage dated c. 575–625 AD, likely belonging to a Kentish Anglo-Saxon woman. Recovered through metal detection and excavation, the find includes richly decorated disc-on-bow brooches with garnet inlays in Salin Style I, silver pins, a plated disc brooch, buckles, rivets, and a rare polychrome bead. The sheer number and detail of brooches—ranging from local Kentish types to variants linked with broader Germanic fashions—make this one of the clearest material reflections of early Anglo-Saxon visual culture and craftsmanship. (Photo: Kent County Council CC BY 2.0)

Long Brooches: Continental Echoes

The earliest Anglo-Saxon brooches in Britain were heavily influenced by the Migration Period styles carried across the North Sea by Germanic groups. Among these were the long brooches—bow-shaped, square-headed, and cruciform varieties. These were based on types used across northern Germany and Scandinavia but developed local distinctions in England. Square-headed brooches, for example, became large and ornate objects in Kent and East Anglia, often cast in copper alloy and decorated with Salin’s Style I animal ornament.

Cruciform brooches, often over 10cm in length, were especially common in Anglian territories and bore stylized animal masks on the footplates, a feature seen across northern Europe. These early brooches were typically worn in pairs and used to fasten peplos-style garments for women, indicating both functional use and high symbolic value.

Saucer and Button Brooches

By the mid- to late-sixth century, disc-based brooches began to dominate. Saucer brooches, made from cast copper alloy with incised geometric or vegetal motifs, were especially common in central and southern England. Their design drew from both Roman and continental Germanic precedents, yet became distinctly Anglo-Saxon in execution.

Button brooches, smaller and typically made of silver or bronze with gilding, featured stamped human faces or animal masks. Some scholars, such as Suzuki, have suggested that these motifs represented deities or spirits, although interpretations vary. The strong regional clustering of button brooches, particularly in Kent and Wight, hints at cultural zones with strong shared traditions.

Materials and Craftsmanship

Anglo-Saxon gold pendant brooch from King’s Field, Faversham (early 7th century). Featuring three cloisonné raven heads in a triskele pattern with cabochon garnet eyes, it is edged with twisted wire and decorated in fine filigree and granulation. This Kentish piece reflects elite female adornment and bears close stylistic ties to contemporary disc brooches of the region. (Photo: British Museum)

Garnet Cloisonné and Gilded Bronze

High-status brooches employed luxurious materials and techniques. The Kingston Brooch, found in Kent, exemplifies cloisonné garnet inlay bordered by gold filigree, closely linked to Frankish and Visigothic aristocratic styles. Such brooches required not only raw materials imported from distant regions (e.g. garnets from India or Sri Lanka) but also specialist knowledge in metalworking. These elite artifacts show the high degree of connectivity between Anglo-Saxon elites and their continental peers.

Silver-gilt disc brooches, like the Fuller Brooch and Strickland Brooch, reflect a shift toward Christian themes in the ninth century. These employ niello inlay, fine repoussé work, and abstract personifications (e.g. the senses), indicating a growing interest in theological symbolism and ecclesiastical patronage.

Workshops and Production Networks

Evidence from mold fragments and unfinished brooches at sites such as Hamwic (Saxon Southampton) and York suggests that brooch production was not limited to elite commissions. Urban workshops likely serviced both secular and ecclesiastical clients. Stylistic clusters—such as the "Kentish style" or "East Anglian cruciforms"—may indicate mobile workshops or itinerant artisans.

Social Function and Identity

Anglo-Saxon belt buckle dating back to the 6th - 7th centuries (Photo: Kotomi CC BY-NC 2.0)

Gender and Burial Customs

Brooches were predominantly worn by women in the fifth to seventh centuries, often found in richly furnished female graves such as at Buckland, Dover, and Lakenheath. Double brooch pairs on the shoulders, along with beads and chatelaines, reflect a Germanic tradition of female display, perhaps linked to marital or clan identity.

By the late seventh century, as Christian burial customs spread, the deposition of jewelry in graves declined. This shift coincides with the rise of monastic culture and a new emphasis on relics over personal adornment. Brooches did not disappear but were increasingly found in hoards or church contexts, as seen in the Pentney Hoard.

Status, Heirlooms, and Repairs

Certain brooches show signs of repair or modification, indicating they were cherished across generations. Some may have functioned as heirlooms or diplomatic gifts. A number of brooches from female graves show reworked pin hinges, suggesting that functionality was maintained alongside symbolic continuity.

Brooches in Comparative Germanic Context

Visigothic pair of raven fibula found at Tierra de Barros, Spain

Gothic Fibulae and Shared Iconography

Fibulae worn by the Goths, especially in the fourth to sixth centuries, show close formal and symbolic parallels to early Anglo-Saxon brooches. Gothic crossbow fibulae and paired disc fibulae feature similar interlace patterns, stylized animal heads, and elaborate profiles. For instance, the famous Visigothic fibulae from Spain and the Ostrogothic disc brooches of Pannonia display cloisonné techniques nearly identical to those found in Kentish brooches.

While it is clear that Anglo-Saxon artisans adapted these techniques locally, the broader Germanic world provided the initial artistic grammar. Scholars such as Hines and Effros have emphasized that Anglo-Saxon brooch design cannot be seen in isolation but must be situated within a web of exchange and imitation that spanned from the Danube to the Thames.

Differences and Local Innovations

Despite similarities, Anglo-Saxon brooches quickly took on regional characteristics. Cruciform brooches with zoomorphic feet are largely an English phenomenon. Likewise, button brooches with facial stamps are rare outside of Britain. The Christianization of design—evident in the ninth-century Trewhiddle style—also marks a divergence from continental fibulae, which retained more overtly martial or courtly themes.

The Trewhiddle Style and the Ninth Century

Named after a hoard discovered in Cornwall, the Trewhiddle style of the ninth century marks a turning point in Anglo-Saxon ornamental art. Brooches in this style, such as those from Pentney or the Minster Lovell collection, feature fine silver openwork and animal interlace with plant scrolls and Christian symbols.

These brooches were likely produced by monastic goldsmiths under ecclesiastical patronage. Their iconography often includes crosses, saints, or biblical animals like doves and lions. This period saw brooches shift from elite female attire to more unisex, symbolic usage, often worn by clergy or upper-status laity.

Strickland Brooch, featuring the Trewhiddle style (Photo: British Museum CC BY-SA 4.0)

Legacy and Cultural Continuity

Though large brooches fell out of fashion after the Norman Conquest, their legacy persisted in smaller dress accessories and church metalwork. The stylistic language of Anglo-Saxon brooches, particularly their use of symbolic interlace and symmetry, influenced Romanesque art and manuscript illumination. Moreover, their study continues to inform debates about identity, mobility, and cultural continuity in post-Roman Britain.

Brooches also serve as a rare point of continuity between the material cultures of Germanic paganism and Christian England. Their evolution—from functional items to richly symbolic artifacts—mirrors the transformation of Anglo-Saxon society itself.

Anglo-Saxon brooches, in their variety and complexity, embody the artistic and cultural vitality of early medieval England. From their roots in continental Germanic traditions to their flourishing in monastic workshops, these objects are keys to understanding how identity, belief, and aesthetics intertwined. Comparisons with Gothic and other Germanic brooch types highlight shared ancestry, but also the unique trajectory of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship. These artifacts, unearthed from graves and hoards, do not merely adorn history—they help define it.

ᚸ

References

Avent, R. (1975). Anglo-Saxon Garnet-inlaid Disc Brooches. London: HMSO for the British Museum.

Backhouse, J., Turner, D. H., & Webster, L. (Eds.). (1984). The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art: 966–1066. London: British Museum Publications.

Brugmann, B. (2004). Glass Beads from Early Anglo-Saxon Graves: A Study on the Provenance and Chronology of Glass Beads from the 5th to 7th centuries AD. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Dickinson, T. (1993). Early Saxon saucer brooches: A preliminary overview. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 6, 77–83.

Evison, V. I. (1987). Dover: The Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery. London: Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England (HBMCE).

Hines, J., & Bayliss, A. (2013). Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the 6th and 7th Centuries AD: A Chronological Framework. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology.

Leigh, D. (1980). Brooches in Late Anglo-Saxon England: The Distribution and Chronology of Brooch Types. Medieval Archaeology, 24, 61–84.

MacGregor, A., & Bolick, E. (1993). A Summary Catalogue of the Anglo-Saxon Collections (Non-Ferrous Metals). Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

Marzinzik, S. (2003). Early Anglo-Saxon Belt Buckles (Late 5th to Early 8th Century AD): Their Classification and Context. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Marzinzik, S. (2013). Masterpieces: Early Medieval Art. London: British Museum Press.

Meaney, A. (1981). Anglo-Saxon Amulets and Curing Stones. Oxford: BAR British Series 96.

Tait, H. (1986). Seven Thousand Years of Jewellery. London: British Museum Press.

Webster, L., & Backhouse, J. (1991). The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture, AD 600–900. London: British Museum Press.

White, R. H. (1988). Roman and Celtic Objects from Anglo-Saxon Graves: A Reassessment. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 1, 109–115.

Wilson, D. M. (1984). Anglo-Saxon Art: From the Seventh Century to the Norman Conquest. London: Thames and Hudson.

"Anglo-Saxon belt fitting 6-7c" by Kotomi_ is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

"Anglo Saxon Brooch" by Giles Watson's poetry and prose is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

"Anglo-Saxon belt fitting 6-7c" by Kotomi_ is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

"Anglo-Saxon disc brooch 6c" by Kotomi_ is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.